Last Spring, I got to catch up with Asger Carlsen, the Danish artist behind the amazing 2010 book, “Wrong,” and the forthcoming Mörel project “Hester.”

Jonathan Blaustein: Why did you decide to move from Denmark to New York?

Asger Carlsen: I was working as a commercial photographer, and signed up with an agent here. They gave me a work permit, so I decided to try it out for a year. It seemed like a good idea at the time. This is five years ago.

JB: Is it the same agent you’re working with now?

AC: Yes, Casey in New York City. I signed up with them 7 years ago and that’s how I came to move to the states. The jobs we did in the beginning where more straight up assignments, but now it’s more based on my artwork ideas with a very strong post production concept to it. I even had one client in in london asking me if they had to provide the image material or if I did the photography part, so in away i’m more “material director” then a photographer. The challenge is to communicate that to the market.

Do You do commercial jobs?

JB: No, I don’t do that anymore. But everything I did was local, out here in the boonies. My skills were never such that I could have done commercial work in a major market.

AC: There is obviously great income potential to be made from the commercial industry- but ultimately I feel more related to the Art Scene and the sensitive forms of art.

JB: Yes, we all need to pay the bills.

AC: Yeah, but even maybe I’ll find something else. Teaching could be an idea, or something that could keep my creative side happy.

JB: Listen, I’ve been teaching for seven years, and the grass is always greener.

AC: Let’s say I want to spend 50% of my time doing Art, (if I could do art full-time I would do it) I could pretty much do anything. Teaching would be interesting, although the money is probably not as good.

JB: No. But it’s deep work, depending on who you’re working with. I want to start with a big question. I don’t know how much time you spend surfing the web, but I feel like there’s an idea that we hear a lot, so much so that it’s almost accepted: Every picture has already been made. Every photograph has already been shot. Every idea has already been done.

I think a lot of people believe that. I don’t. I strive to innovate, myself, but I think that anyone who looks at your book “Wrong” can’t believe that anymore.

How do you feel about innovation, and finding an original vision, as opposed to doing what everyone else is doing?

AC: It’s definitely the challenge. Like you, I’ve heard it many times before. Every picture has been taken.

When I started the project, the first couple of images, they were so different from my aesthetic, the direction that I was heading, so I didn’t show anyone the images for a whole year.

I don’t want to say that this is the newest work, and it’s so different from any other artwork you have seen. But that was the most important thing for me. The reason why I did continue that style, although I found it was not my aesthetic. It was important to me because it was new, compared to any other direction I had headed before.

So in away the innovation won over whatever problems I had with my new discovery. I also found out by working this new approach

The core of my work comes out of arrival materials or props I build in my studio. For my latest project all the materials is very short photo sessions with models done mostly in my studio.

All these photos becomes a pile of materials that I can work with in my studio. That new approach allowed me to be a hundred percent creative in my studio. Because I didn’t have to run out and find that one special picture to capture. Because I’m now mostly driven by ideas around that martial and in away it become my everyday knowledge.

JB: You say it was very different from your aesthetic, but you made it. What aesthetic of your own were you contradicting?

AC: You know, the way that you work as a photographer is that you pick a style, and then you continue down that road, and you try to stay consistent, because that’s the way you become known for a style, or get work, or become a good photographer. You can copy that style over and over.

I had a very straight style, more inspired by what they do in Germany. The Gursky, kind-of-landscapey photography.

JB: Does that loom over the Danish scene?

AC: You know, ten years ago, that was the photography that people were looking at.

JB: True.

AC: You know, large-scale formats, landscapes, Thomas Struth & Thomas Ruff, all those people. I’m sure you were inspired by those too.

JB: Sure. You were doing that work, showing it to the world, and then, in your little computer room, you were hiding away, working on your mad projects.

AC: I was almost embarrassed by the first two images. I didn’t show them to anyone. In the end, I thought it was more important to create these new things. Maybe they were not pretty images.

JB: No. They’re not pretty.

AC: They’re not photographic beauties, which was the aesthetic for that time. You were supposed to do really detailed landscapes. You would find this perfect viewpoint where you put up your tripod, and took these images.

JB: And I read in another interview that you were a crime scene photographer?

AC: People sometimes get that confused. I was a crime scene photographer, but that was when I was out of high school. So I was 17, and then did that for ten years.

JB: Who did you work for? A police department?

AC: Newspapers. I was a full-on newspaper photographer. I started out as an intern, and saw how it was done. Then I bought a police scanner, and would respond to the calls. Car accidents and stuff. Eventually, I did photograph a bit for the police.

JB: You’ll have to forgive me a bit here. My wife is a therapist, and my mother-in-law is a therapist, and now, being an interviewer, I’ve kind of morphed into this guy who tries to read the tea leaves. It sounds to me like there was a lot of darkness going on in your job, and in your head, and all of a sudden, it popped up out of the shadows, into this style that became “Wrong.”

AC: Certainly, there is an understanding of how those crime scene scenarios could look like. The work certainly represents my time as a newspaper photographer.

You can dig into that. You can see how I was standing in front of a car accident, photographing it. It’s just different objects.

JB: Did you photograph in Black and White for the newspapers?

AC: Yeah, it was all in Black and White. It sounds so long ago. This was the early 90s, and there was no scanners or anything, so everything was Black and White. The newspaper that I was working for, when I first started out, could only print color on the weekends.

JB: When I first saw “Wrong,” which I reviewed for photo-eye, I went to the whole sci-fi thing. They’re so techno-futuristic. William Gibson. Paul Verhoeven. I think I dropped “Total Recall” in the book review I did about it.

AC: Yeah.

JB: At the same time, it’s almost like Weegee meets William Gibson. Old school, Black and White man on the scene aesthetic meets techno-futurism. A pretty original mashup.

While you’re not saying it outright, it becomes easier to see what the steps were that led you to an innovative breakthrough.

AC: For me back and white is very sculptural and that helps then become more like objects, which is part of my ambition about the work…. I have a lot of interns here, and when you talk about Black and White images, and the way they were printed, and the way you technically shot them, because you could only do certain things in a darkroom. They just don’t have a clue what I’m talking about. Do you know what I mean? The work is done that way because I understand that sense, and that quality.

JB: I have some students, and we were looking at some work last week that was really super-digi. Over-saturated, hyper-real, hopped up, textured and degraded. I talked about that, and these are younger students, and they couldn’t see it. That archive that we have in our head, of the cinematic and celluloid look, they don’t have that baseline. Their baseline is digital reality.

They can’t tell the difference between the super-saturated color look on the screen, and what you see when you walk out your door. Their brains are just different now.

AC: They are different. Do you think they understand my work differently than you understand it?

JB: Sure. I would think they have to. I showed “Wrong” to students last year, and they ate it up. Ate it up. I’m curious to see what happens when this generation of students, who has only grown up in the digi-verse, when they’re mature enough as artists to make shit that we can’t even imagine.

AC: I’m sure in ten or twenty years, the files being produced by these random Canon cameras, that’s going to be a style that people will try to copy again.

JB: The sci-fi reference in “Wrong” are so strong, and I don’t even consider myself a sci-fi geek. What did you read or see that ended up percolating into your work.

AC: I was inspired by painters, different art movements and all these obvious classical references. There’s a certain awkwardness in the work, and maybe that’s my attempt to try to fit into a photography style. Part of the reason why I became a photographer is that there was a certain loneliness in it, a searching for something. I think the work is a bit about that as well.

Trying to find my spot. Maybe I am a dark person? (Thinks about it.) I am a dark person.

JB: You certainly have it in there.

AC: I felt like an outsider when I grew up, for sure. There are certain things I’m good at, and photography is one of them. But I was not a success in school, not a success in many things, but there was this one thing I could do.

JB: So you were an artsy kid?

AC: Yeah. Maybe I said in an interview that it was my attempt to try to belong somewhere. I would say that there is some subconscious influence to the work as. That could refer to who i am and what live i lived.

JB: That sounds like something someone would say in an interview.

AC: (laughing) I’m still saying that.

JB: It’s funny, but the question was about sci-fi culture, and you didn’t really address that…

AC: Of course, I find Star Wars and stuff like that, Total Recall and Blade Runner, I find that stuff amazing, aesthetically. They’re not totally 100% perfect, but they have something else. Of course, I’m inspired by this Universe that can lead you somewhere, but is not an entirely precise realty.

JB: They do say that Science Fiction, historically, was like an Allegorical playing field. By stepping out of reality, it allowed certain authors and filmmakers to comment on a cultural moment in a way that was abstract enough to give cover to talk about real things. If we were going to say that about you, then the work casts a scathing eye on genetic modification, and the slippery slope towards cloning. The photos make it seem so real.

And yet, using the wooden legs, and bringing in the low-tech, was just badass. Do you talk about contemporary culture, when you talk about the work, or do you try to let the pictures speak for themselves. What’s your take on that?

AC: In general, I try to let them speak for themselves. People often have different interpretations of the same images. But I’m trying to be cultural commentator. If anything I’m trying to remove it from looking like contemporary. But there is a certain openness in the stories and maybe should be to explain.

JB: Ambiguity is crucial. We want to have enough information in our pictures that people really get where we’re coming from, but not so much that everything is tied up with a bow on it.

Do you have an artist statement for “Wrong?” Do you find yourself having to talk about it and write about it? That’s another buzz-worthy topic. A lot of photographers are caught in between this desire people have for us to be able to write and explain everything, as opposed to being simply visual communicators.

AC: Yes I don’t have to talk a lot about the work informs of interviews etc. I think a lot of creativity comes from a place there is hard to realize. I personally don’t always have the need to over read about why an artist made the choice of work that he did. Do you know this application Instagram?

JB: I do.

AC: Do you use it?

JB: I don’t.

AC: I use it a lot, and I think it’s an amazing application, because it’s just images. People can leave small comments, but it’s just pure images. Pure visual observations. I find that really interesting. I don’t want to hear the information about how the picture was captured, or the ideas behind it. That’s just how I am.

JB: I don’t use it, because I don’t have an Iphone. Instagram seems a little superfluous with my janky little LG phone. I’m glad you made that leap. Unexpected. But if we’re going to leap, why don’t we leap to the new work.

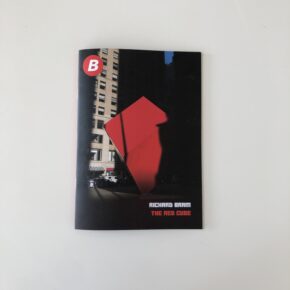

You have a new book coming out with Mörel Books called “Hester.”

AC: That is correct.

JB: This is your second book with them. Was it always your goal to have your work presented in book form?

AC: I have no plans, for better or worse. It just happened. This “Wrong” project, I just did if for myself. I didn’t have any hopes that it would be a book, or an exhibition, or anything else. I just did it without thinking that I could have a reaction to anything or anyone.

Then Aron Mörel of Mörel Books emailed me and asked me if I wanted to do a book with him. It took off from there. Kind of unexpected. I think Kanye West blogged about it, and I had massive emails and hits on my website.

JB: So are you down with the champagne lifestyle now? Are you partying with Kanye and Jay-Z?

AC: No. I live a pretty normal life.

JB: How will “Hester” fit alongside “Wrong?” Are they companion publications? How did you go about planning the second book?

AC: They’re definitely linked. The new work is more sculptural. In my artist statement, I say it could be a photograph of a sculpture, more than real photographs.

JB: Are you carving foam in all these images? Certainly in “Wrong,” there are all these creations. Are you making things with your hands, in your studio, and then over-laying it? Or is everything coming out of the computer?

AC: All the weird shit is coming out of the computer. Except for “Wrong.” Where I built all the props myself.

JB: You did.

AC: Wood, foam, meat, metal. They’re hanging here in my studio. I built them in my kitchen in my Chinatown apartment.

JB: What happened when people came over?

AC: My apartment was crazy at that time. All the walls were covered with references, and props that I built.

JB: It sounds like it was a pretty organic extension of who you are and what you care about.

AC: Yes. It was a turning point where I left my old routines as a photographer and started something I was not quit sure of at the time. like I couldn’t hold it up against anything. It just felt important for me.

JB: That’s a part of the philosophy. It has to be personal, and it has to be important, and it has to be authentic to us. One place where people do get caught up in being derivative is they’re making their work based upon what they’re seeing in the outside world. People they want to be like. They’re more reacting than creating.

AC: Yeah, I hear that all the time from my interns. They’re talking about this photographer, and that photographer. Two days later, they show me an image that they almost copied.

I just did this work because it felt right for me. It was the ultimate way of expressing myself, telling the world who I was, and what I found interesting or funny. I wanted to use photography in a way that it wasn’t used before or at least make the attempt.

I didn’t want to become Ryan McGinley, or someone.

JB: But both he and you have both photographed Tim Barber, so you do have that connection.

AC: Yeah, and we both live In Chinatown

JB: I had no idea.

AC: But the point I’m trying to make is that I wasn’t trying to be someone, or care about that stuff. It was just a piece of work that I wanted to do, and I had a lot of fun doing it.

JB: It comes through. Experimentation and risk-taking are ultimately what lead people to innovate. You can’t know what it’s going to look like before it’s done, in the beginning. You have to feel your way towards things that you don’t know how to do.

But I want to shift gears for a second. There’s something I want to give you a hard time about. You live in New York. You’re used to it.

AC: Give it to me.

JB: Some of the most striking images in “Wrong” depict nude women. Naked people. Your publisher, Aron, even told me, when I pointed it out, that one of the nudes is the best selling image.

In “Hester,” it’s all naked women, fused together with you. Is that right?

AC: Yes a pile of images of different models collected (photographed) over time. Including images of my own body like muscles, and my bone structure. For me its just process of gathering martial.

JB: It’s Frankenstein Art. But I also saw something on your agent’s website where you did another series for “S” Magazine where you did a whole set of manipulated nudes. Boobs on butts. That sort of thing.

AC: Right.

JB: So here’s what I want to know. I saw on Twitter last week, where the Guggenheim was doing some Twitter promotion about the John Chamberlin exhibition. One tweet said something like “Chamberlin said his work was not about America’s car culture.” And my response was “Bullshit.” An artist can say whatever they want, but ultimately, if they’re good at what they do, the communication comes from the work itself.

AC: Sure. I also think that abstract expressions doesn’t need a concert reference. Other then maybe subtle gestures.

JB: So, you’ve been photographing a lot of naked women. But in one of the interviews I read with you, I have a quote where you said, “I have no desire to photograph naked girls.”

AC: I have no desire. That’s true.

JB: And yet you do it?

AC: And yet I do it. I can defend it.

JB: Cool. I was hoping to get you defend the statement. Especially as some of the women, at least before they were genetically modified, seemed to be young and attractive.

AC: Some of them were very young and attractive. I have no desire to photograph pornography, or naked women. No desire at all. Except for project I did called homemade that gives very strong associations to porn. But in fact most of the props I used was totally unrelated to a sexual realty. Like an empty illusion.

JB: OK.

AC: my intentions was to create something timeless that wasn’t interrupted by contemporary culture. So, the choice of not having any clotting seamed necessary. Like more as seamless and sculptural statement.

JB: But you’re also keeping it within the continuum of Art History. People have been drawing, painting sculpting the nude body forever. Is that a part of it for you, to make it a Post-Post-Modern, Post-Punk version of Classicism?

AC: Yes it could be be post post modern, hester has strong sculptors ideas and i guess I’m trying to prove that there is no difference from a sculptor working in clay and shaping his sculpture from me working on my digitizer. I think if you work with photography in a way where you build forms and shapes in the traditions of art history I could be perceived as sculptural art. I know a print is still a flat surface, but my hope is that it will gain a value as an object.

JB: I have to think about that.

AC: It’s just different materials. It’s just because photography belongs to a certain idea, and there are certain people doing it. I think that doesn’t have to be true anymore.

JB: In every interview I’ve done, give or take, we always end up coming back to this idea of the words we use to describe what we do, whether it’s journalism vs art, or documentary vs art, or sculpture vs photography. It’s almost like people get so caught up in the language used to describe the objects that it detracts from people looking at an object and just taking what’s there.

AC: But isn’t that the problem with photography, still. Do you think? If you take it into the Art World, photography is still considered something on the low end, compared to someone who is doing drawing or painting.

JB: The biases do persist.

AC: Maybe people are getting over it. But then, I have been talking to a few high end photo galleries, and they all seemed very interested, and in the end, they all come back to me and said they don’t think they can sell their work to their photo clients because it’s too far away from photography history. The idea is not consistent with what you would expect photography to be like.

JB: This Spring, I was in Houston for this big photo festival, FotoFest, and I had at least five people ask me whether I thought my work should be in an art gallery instead of a photo gallery.

But this idea that photo dealers can only sell work if it’s attractive and conservative, and the further out it gets, the more it has to be consigned to into the Art World. It doesn’t seem very representative of today.

AC: Well, I know a huge gallery in London, which I won’t name. They represent big, famous, established photographers. I think it has to do with money. A lot of what they do, where they make money, is vintage photography.

They’re afraid if they bring in something like this, they’ll scare away their clients. That is the feedback I’m getting.

JB: Do you take that as a compliment?

AC: Yes, but it’s also a little sad.

4 Comments

Thanks for posting_inspiring for sure.

Like it or not, he gets an “A” for originality. Not a lot of us can say that.

These photos remind me of one of my FIT photography professor’s work — Alfred Gescheidt. Here’s a link to some of his better known photos: http://www.higherpictures.com/artists/Alfred_Gescheidt/Works.aspx?s=201&i=1

The first day of class he photographed each student. At the next meeting he gave each of us the photo he shot. Still have mine. Wish he had Gescheidt-ed it.

Asger work takes the approach to a whole ‘nother level, and goes to a scarier place — like Twilight Zone for grown ups. He shows us things we know exist but would like to pretend do not.

Fantastic, many thanks for this Jonathan.

Comments are closed for this article!