For those who haven’t been following the major rift in the world of photojournalism a quick summary of what is going on: A film called “The Stringer” directed by Bao Nguyen (previously directed The Greatest Night In Pop) and produced/starring Gary Knight (VII Agency co-founder and ED) premiered at The Sundance Film Festival on January 25 claiming and attempting to prove that 53 years ago Nguyễn Thành Nghệ actually took “The Terror of War” (AKA Napalm Girl) image and not Nick Ut. AP photo editor Carl Robinson claims his boss, Horst Fass, told him to switch the credit from Nguyễn, a stringer, to Nick, an AP photographer. The filmmakers find Nguyễn, and he says, yes, he took the picture.

Prior to the film’s premiere, the AP released a preliminary report disputing the claims of the film. At the premiere, the AP watched the film and followed up (May 16) with a 100-page report saying that there’s not enough evidence to remove Nick Ut’s credit.

Then, on May 16, World Press Photo released a statement saying they investigated (David disputes the characterization that they investigated and rather they simply got a private screening of the film and agreed with the conclusion) and are suspending Nick Ut’s credit on his 1973 Photo of the Year award.

This sparked outrage on social media with posts from what appears to me to be the VII camp (Ashley Gilbertson, Ed Kashi, Sara Terry) and the Nick Ut camp (David Burnett, Pete Souza, David Kennerly).

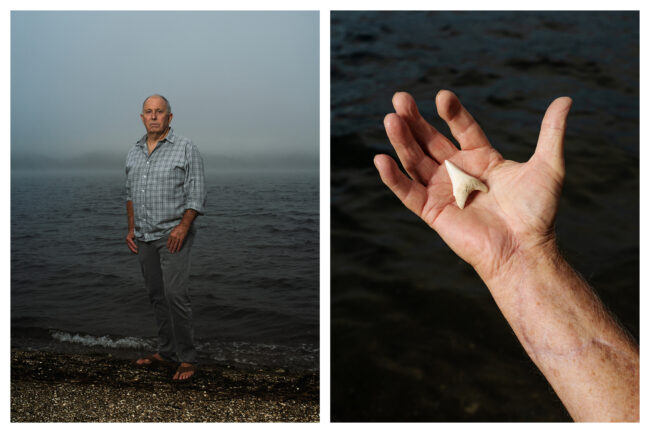

And the real zinger in the whole dust-up is that David Burnett was there! He’s an eyewitness to the events at Trang Bang, where the famous image was made.

Ok, one final note: besides the premiere at Sundance and private screenings, the film cannot be watched until a distributor is lined up. I’m aware of a screening in DC next month, but most people, including David and myself, have not seen the film.

I talked with David over the phone, and here’s a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

Rob Haggart: I want to start by asking if it’s really difficult for you to go back and rehash all this stuff.

David Burnett: No, I mean, I have these moments from not just Vietnam, but the jobs that I worked my whole life, French elections, Ethiopia, Chile, and it’s not really something that causes me great pain. There are so many of these things that I’ve lived through that the memories of them and what I was doing in them as a photographer is very, very clear in my head. And Trang Bang is really no different than almost anything else.

The first time I was under fire and had the crap scared out of me, it’s one of those things where you don’t just think, will I ever get over it? Because you don’t, they become part of what your life is about.

The running joke about Trang Bang and me was that, well, I missed the shot because I was changing film in my old screw mount knob wind Leica which is kind of a slow, kludgy film camera. It was not an easy camera to operate.

And yet, Cartier-Bresson shot with them for something like 20 years before the M2 and the M3 came along and made some pretty great pictures, so I mean, I think part of why I even bothered shooting with that camera instead of getting another M2 for 200 bucks, was kind of a historical thing with the old Contax and Leicas, you felt a little more attached to some kind history if you’re shooting with this kludgy old camera and um you know, and I was trying to reload it and anybody had ever owned one of the cameras knows that if you take a 35-millimeter film where you have the little cut-down tongue that you really need to cut an extra inch or inch and a half away from that one side that’s cut so that when you drop the film in the camera, it will seat itself perfectly.

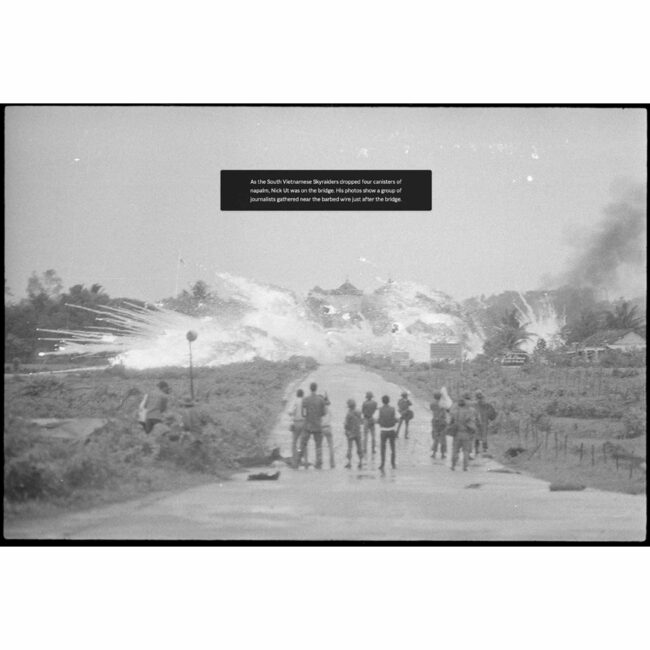

I never bothered doing that, so I was always stumbling, trying to get the camera reloaded. So I was reloading it when the plane came in to drop the napalm. I was holding the open camera in my left hand and shooting with a 105 in the other hand. When the napalm hit right next to the pagoda, there was this Gigundo fucking fireball, Nick has that picture, and I kind of have it a few seconds later. But it was the in the days when you didn’t shoot with three motor drives, you know, you weren’t going out there to shoot 25 rolls of film. I think I shot maybe three or four rolls that day, and it was a fairly long period of time we were there because we were kind of hanging out waiting to see what was going on.

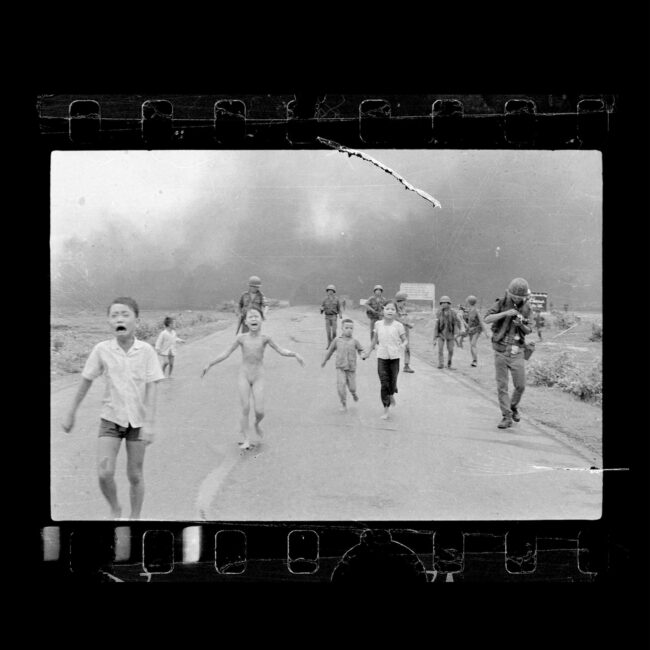

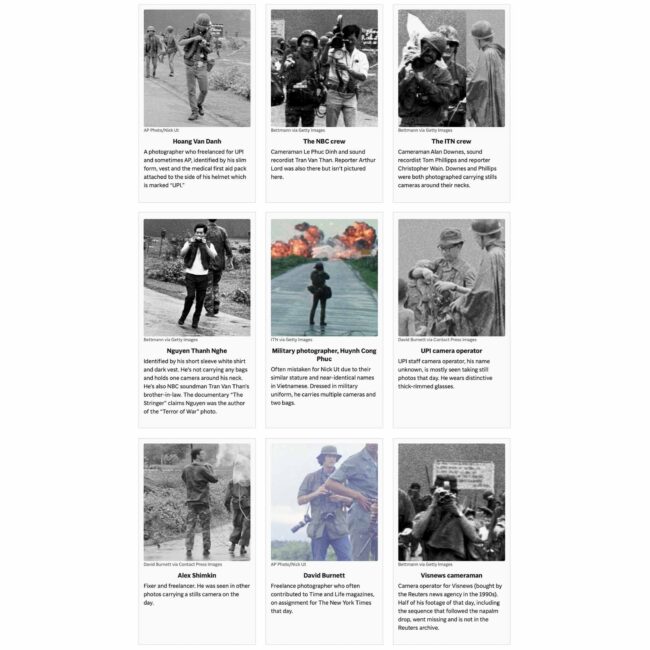

You could hear firing and shooting coming from the village. Then the planes came in, and there was that fireball, and then like three minutes later, the kids started running out of the field and onto the road toward us, and that is the moment, more than anything in my mind, where Nick was the one guy who was in a position to shoot the picture, and nobody else was. There was this line of journalists, and we were all within a few feet of each other lined up across the road. As soon as we could tell that, there were people on the road racing out toward us, and the kids were running as fast as they could run. Nick and this guy Alex Shimkin, who was killed a few weeks later up north, took off running towards them, and no one else did.

RH: When did you first hear a film was being made about this event and that there were questions about the author of the famous image?

I was sitting at a Walgreens parking lot in Florida 3 years ago going in to go get some stuff, and Gary Knight called me and said tell me everything you know about Trang Bang, so I spent a couple hours on the phone and told him everything I know and then said you know there’s this guy and he’s kind of a horses ass, ex AP guy and he says that Nick didn’t shoot the picture and I kind of think he’s full of crap as does everyone else but along the way you’re gonna run into Carl Robinson.

Carl had this real chip on his shoulder about AP, and he was never afraid to let people know how he felt like he’d been screwed over by the AP.

RH: So you’re telling me this rumor has been around for a while?

Yep, a long time. It’s not new. The last time I saw Horst Faas was in 2008. There was a gathering for a memorial wall at the news museum in Washington, and if you lived near the East Coast and worked as a journalist in Vietnam, you pretty much were there that day. Somebody at that point could have said, hey, Horst, let me talk to you about this thing that Carl’s been telling everybody that you told him to put Nick’s name on the image, and it was really some stringer’s film.

And no one ever, no one ever asked Horst.

No one ever just asked him point blank.

I guess Carl makes a pretty reasonable case for trying to talk about how the guilt of 50 years and being able to unburden his guilt when he finally met this guy. But you know, every crackpot theory that ever was has at least a 2% chance that it happened.

Could Horst have said it? I suppose he could have. But it would have been very out of line with what always happened.

If you talk to Neal Ulevich, who was in the AP bureau as a staff photographer for, I don’t know, six or seven years in Asia and was in the bureau the whole time, he will tell you about the sacrosanct policy of never allowing anyone’s film to have any name on it other than the actual photographer that shot it.

He said, “All the time I was in Asia, never once did I see anybody do anything like that.”

It just didn’t happen.

I was in that group of people who were looking at the first print of Napalm Girl when it came out of the darkroom, and I did what every photographer in the history of photography would have done, which is I look at this picture and I try and think to myself without having seen my own film, hm, I wonder if I have anything better. I’m thinking, yeah, that’s pretty good. That’s probably better than anything I have.

There were 3 or 4 of us looking at this little 5 x 7 print that was still wet, and Horst, without making a big deal out of it, just turned to Nick and said, “You do good work today, Nick Ut.”

I still have the memo I wrote when I went back to my office at the Time-Life Bureau. I said there was this accidental bombing in this village called Trang Bang, and I said, Nick from AP got a pretty good picture, and they tell me they’re shipping the negative to New York on what’ll be the same flight that my negatives are gonna be on, so you’ll be able to get an original print made in the lab rather than rely on a wire service photo.

So that’s what they ended up doing. It was in the front section of the magazine called the Beat of Life; there were always 3 or 4 of these big picture spreads.

Usually one picture, sometimes two or even three, and they ran one of mine of the grandma with the burned baby and Nick’s picture side by side, and when you look in the photo credits, it says page four and five, David Burnett, AP. I mean, it was the wire services in the 70s. They weren’t going to put a photographer’s name on it. It’s kind of funny that way.

RH: What are the chances, if you’re Nick, that you don’t know beforehand you made that picture?

There’s no way that either of those guys would not know they took that picture. It was such an enpassant moment, and I’m sure there was just one frame that was the one.

For sure, there are times when you’re surprised by something you’ve done when you move from wherever you shot it, and now, you know, we’ve kind of shut out the middle man, and you go right to the computer and see if what’s on there is anything like what you remember, but in the film days I would find it really hard to not know that you had something.

I can’t imagine that the camera wasn’t up at the eye; it’s not like a chest-high Hail Mary, although technically, it was never great, but maybe at the same time, some of the imperfections add to the raw reality of that moment.

RH: That leads me to this talking point I see from the film’s defenders saying that this is not a critique of Nick, but that would mean that Nick didn’t know he took the photo. But you think there’s no way he didn’t know he took the photo, so the film is saying he’s been lying for 53 years about this.

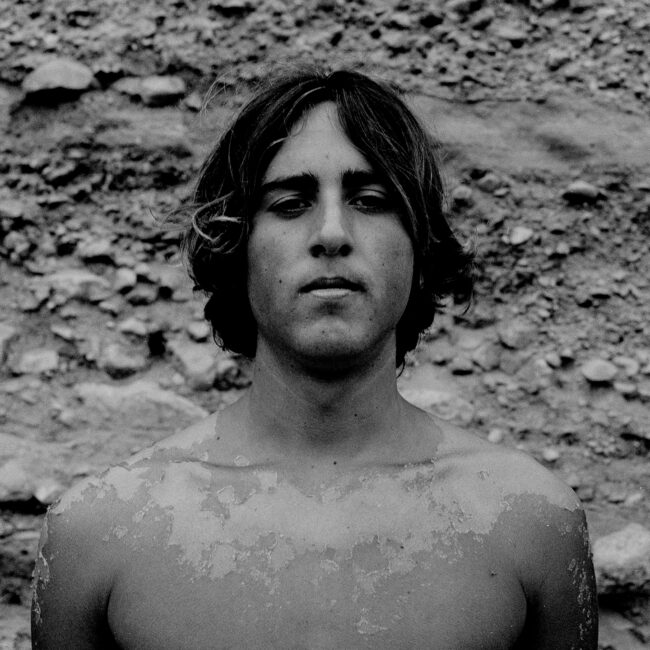

He’s a 21-year-old kid with a camera, and I think incapable of that. Yes, it was a good picture, but there were a lot of good pictures out there.

And, you know, some people have said, oh, but Horst knew right away that that was gonna be a great picture, and he wanted AP to have the copyright on it instead of a stringer. But the thing is, you’ve got all these little sub-arguments if you accept a certain premise, and you can walk yourself right off a cliff of trying to figure out what it is you believe or don’t believe.

Gary called me back at one point, and he said, you know, I think there’s really something to Carl’s statement here, but you know, once you get the first bit of the Kool-Aid, you just gotta drink the whole pitcher, and I just don’t see it.

I mean, like I said, it’s possible.

Everything’s possible, you know?

I mean, you know, once you start to believe part of it, you kind of end up believing the whole thing, or you believe none of it.

To me, it looks like Gary’s trying to make himself into a big documentary producer, and this is his launch pad.

Gary said you ought to be in the film, and I just said, Gary, I don’t wanna do a goddam Mike Wallace interview where I have no control over how you cut it or anything else. I’ve watched 60 minutes too many times where Mike managed to hammer somebody, and I had no confidence that it would be a fair representation.

Fox Butterfield was the reporter I was with that day working for The New York Times, and he got a call from Gary’s wife, a producer on the film, he started to tell her his version of what took place, and she told him everything you’ve said is wrong. That’s not a really good way to coax people into a discussion. She said he would have to sign a non-disclosure agreement, and he said, what the hell for? I’m the one telling you stuff; you haven’t told me anything.

Gary said to me last time I talked to him like six weeks ago, he said, well, you know, we’ve done all this forensic stuff, and we’ve proven that he couldn’t be down there to take the picture.

And I said to him, in my mind, because I remember the way he ran out on the road ahead of everybody else when the kids were coming down the road, he’s the only one who could have taken that picture because it was in the very first moments that the kids were coming down toward where the journalists were lined up, and it was after that everybody else started wandering around, but that was another five or ten or 15 minutes later.

And I just don’t see how anybody else was out there in front, and to me, that picture was taken out in front. It wasn’t taken right next to the press people.

It was out there away, maybe, I don’t know, 20 yards, 40 yards. 50 yards.

RH: How do you think the filmmakers should have handled this? What should they have done with the information they got from Carl?

You don’t ever want to get to a place where people are afraid to posit things, but I don’t know what the answer is, but you know, unlike a lot of people who don’t shut up about it, I’m not sure I have an answer to what the most perplexing question is.

And I never said I was right behind him when he shot that.

I saw him, I was changing my film, and it was a minute or two minutes later, and in those moments, that could be a long time. I offer it strictly as a witness to what happened that day and nothing more.

I find one of the most curious things of all, aware of the fact that Nguyễn probably had to leave Saigon with almost nothing, that he left everything behind, and I totally get that.

But apparently, he never sold another picture to anybody, and in the last 50 years, no one has even seen one picture that he’s taken.

Other than the most famous picture of the Vietnam War.

That is a really weird leap of faith.