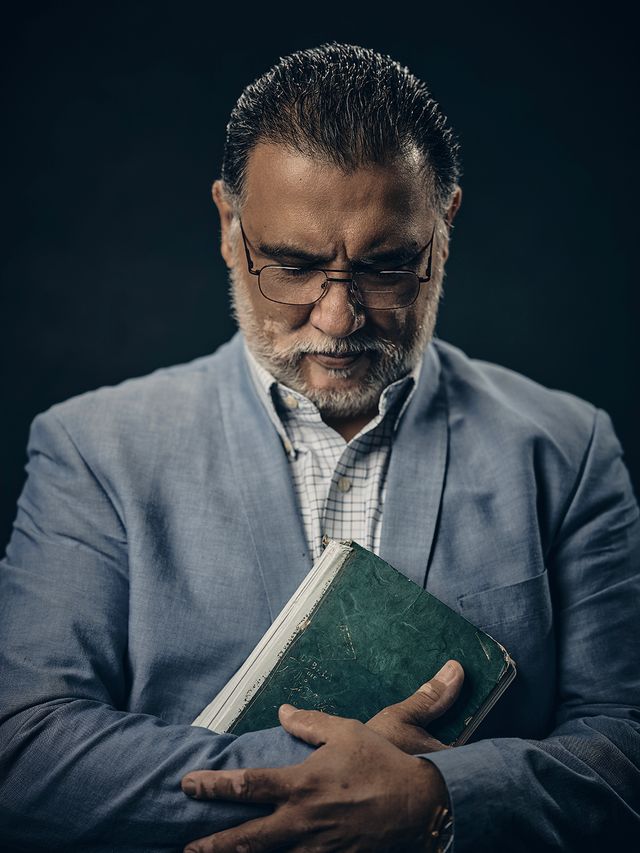

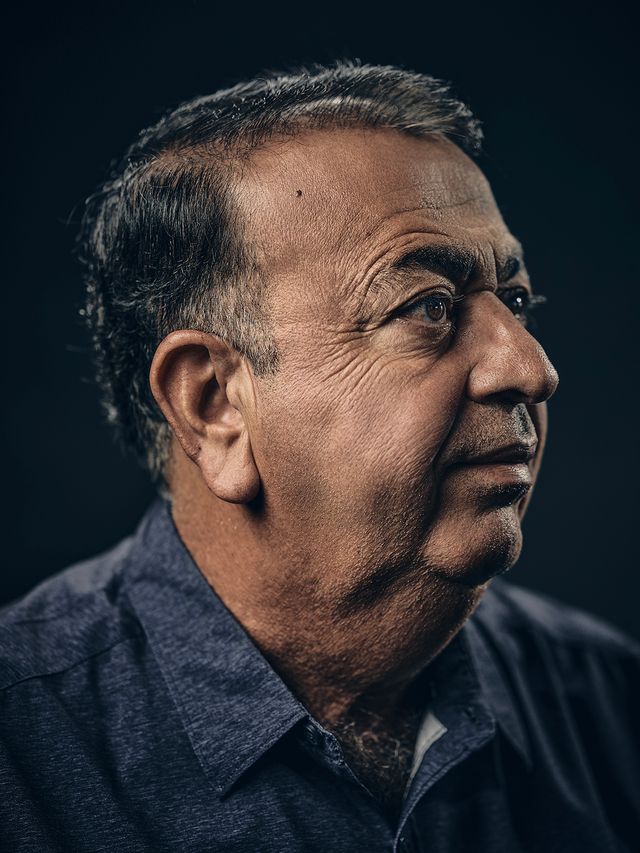

Michael Bednar

Heidi: The Condor & The Bull aims to document the culture of the indigenous Quechua people of the Andes. Describe your vision for the project?

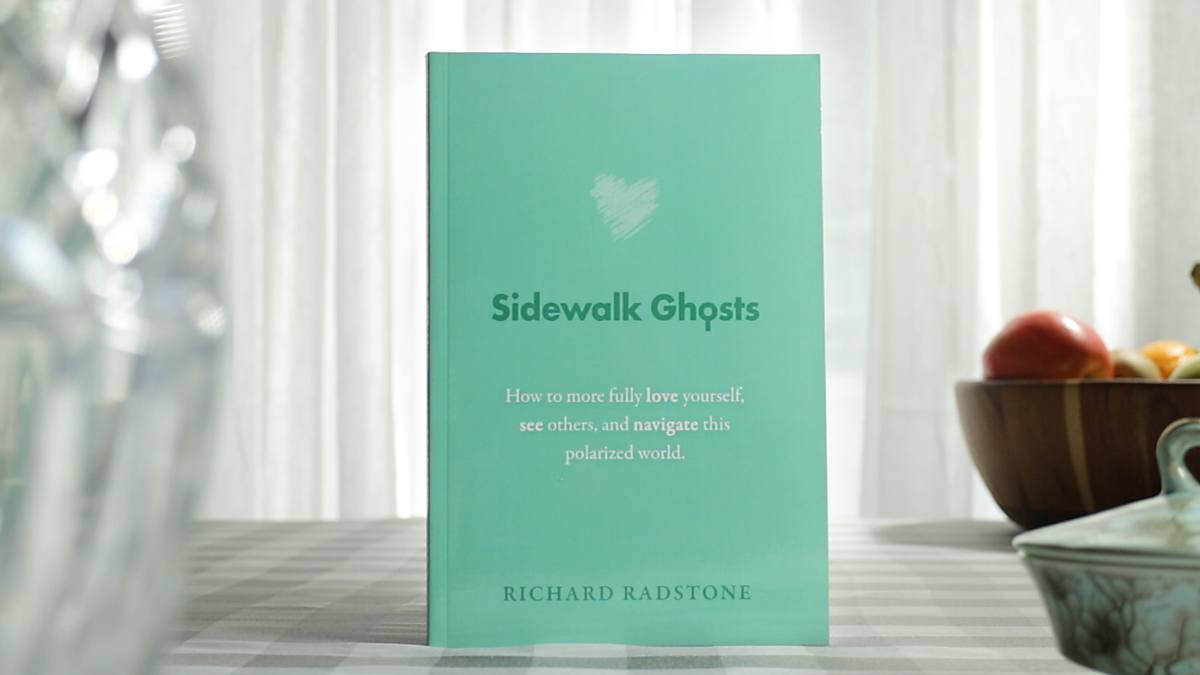

Michael: I intend to make this work into a photo book, which will incorporate narratives and text in English, Spanish, and Quechua. I aim for there to be accompanying exhibitions of the work along with artist talks. This will allow me to reach the widest audience possible. At the heart of this project lies the concept of Ayni, a foundational element of the culture. Ayni embodies the principle of reciprocity, which is vital for both individual and collective well-being. The belief is that balance is achieved through mutual exchanges—whether among individuals, within communities, or between people and Pachamama, the Earth Mother. Historically, prior to European contact, concepts of commerce and ownership were virtually non-existent; life was anchored in reciprocity with communities functioning as collectives. Although the Quechua people have adapted to the realities of capitalism and ownership, the essence of Ayni remains deeply woven into their societal fabric and often stands in contrast to contemporary systems. The project explores the ways which this is represented and how the two cultures co-exist yet move in tandem. From there the narrative examines the challenges the Quechua are facing, mainly in the form of climate change and rapid globalization along with the resulting impacts of these threats. The storyline will ultimately progress to how these issues are being confronted, what ways are the Andean worldview and accompanying traditions and beliefs being carried forward, and how does the culture endure. The world is rapidly changing at the moment and this is a significant time for the culture and the region, which is why felt this to be an important juncture to document.

How do you document or help sustain Quechua traditions under threats like globalization, climate change, and urbanization without treating them as fixed in time?

Cultures are continually evolving and never remain static. They are ever changing. This is seen in the Quechua culture, which incorporates Catholic and Peruvian nationalist symbols into their own customs which express their Andean worldview. This adaptation has allowed their traditions to endure over the past 500 hundred years of colonization. The key to cultures like Quechua enduring is through language and the knowledge contained within it. Currently, it is estimated that another language goes extinct approximately every two weeks along with the knowledge of their environment, their connection to the Earth, and their way of viewing the world. Globalization is a significant driving force behind this phenomenon, acting much like modern-day colonization. Multinational corporations and the wealthy nations in which they are based seek resources in remote areas of the world, exerting their influence over developing countries. This often results in minimal benefits for local populations, who bear the brunt of environmental degradation and the erosion of their human rights. These communities are frequently on the front lines of climate change impacts as well. Consequently, urbanization occurs as individuals are compelled to leave their communities in search of better opportunities. This migration leads to a decline in the number of speakers of their native languages and ultimately contributes to the extinction of those languages, along with the loss of their unique perspectives and traditional ways of life. So, although cultures indeed evolve, they should have the right to self- determination and not have another culture imposed upon them as is currently taking place globally. The end result of that would be a homogenized culture, diminishing the richness of diversity that benefits us all.

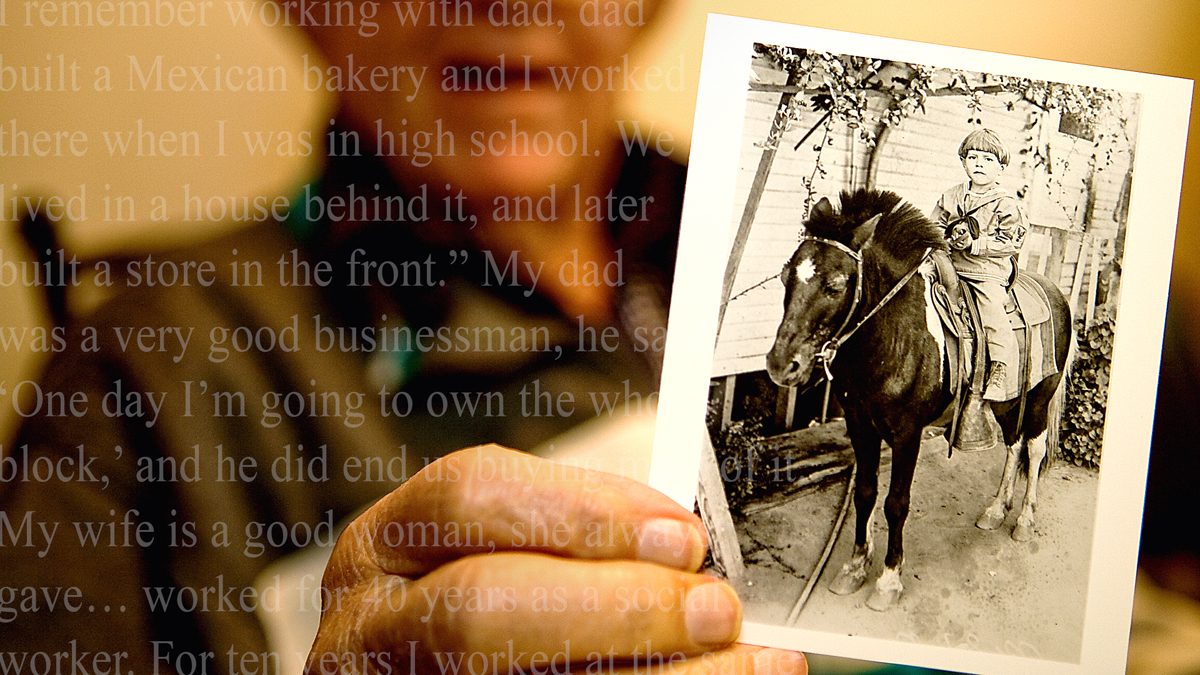

People who suffer the most from the changes imposed upon them are also the ones who gain the least. High-elevation alpaca farmers are not the ones who caused the glaciers they depend on to melt, but they are the ones who are affected and forced to deal with it. Neither are the communities facing drought and water scarcity, and the mining that is dividing communities primarily benefits outside parties who do not have to deal with the long-term effects and environmental degradation it leaves behind.

How do you build trust and relationships with individuals and communities as you document their lives and culture, especially given the sensitivity and privacy concerns around indigenous communities?

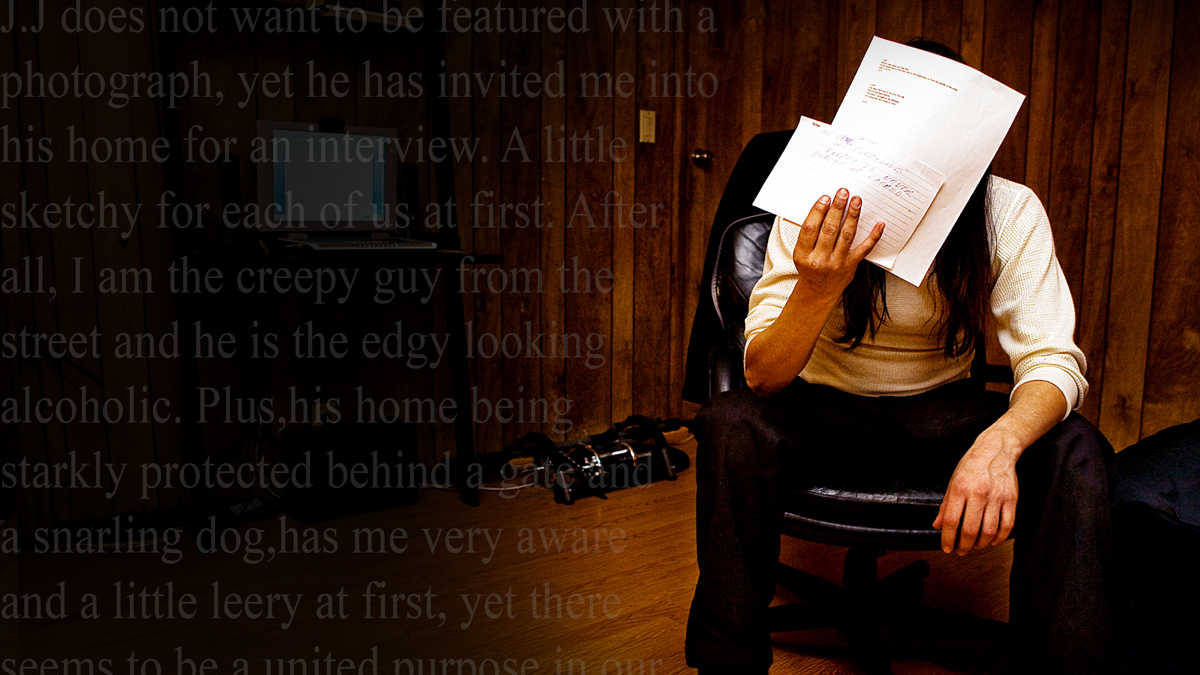

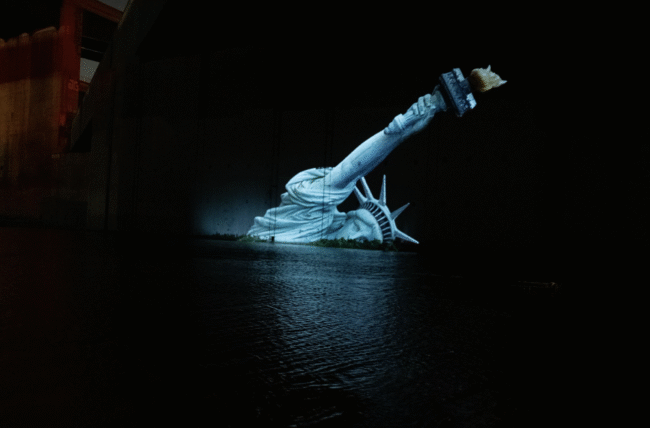

Building relationships and trust takes time, which is not allotted to photographers on assignment these days. Giving this project the time it needed in order to do it justice was important to me, which is why I decided to do it on my own. The origins of this project came as a result of spending time in a community volunteering for a non-profit medical organization over a decade ago. I would spend my free time, often before dawn, and in the evenings, walking and communicating with people in the fields, connecting and learning. I began to understand the challenges the people faced as the two cultures co-existed. At the end of the medical campaign, I was invited back to the community to attend Yawar Fiesta. This festival holds significant cultural importance, as it pits the condor, representing the Quechua people, against a bull, embodying the Spanish rulers, being symbolic of this ongoing struggle. It was this invitation that opened the door and led to the title of the project. It took me eight years to get back to Peru and to begin work on the project. On the day that I arrived in Cusco in December 2022, Peruvian President Pedro Castillo was arrested and imprisoned after attempting to dissolve Congress. Castillo is a Quechua man from the Cusco region, and the people rose up in protest against the government, feeling like their indigenous voice had been stolen. I documented the unrest for the international press for several months, listening and learning to people’s stories and slowly understanding the issues. This would be how I initially built trust and which led to invitations to communities and events to learn more. The vast majority of the time, this is how things have developed; I am invited to communities and events through the relationships and connections I have built. I also collaborate with non-profits and organizations working with communities that are facing many of the challenges I am exploring, especially those that give a voice to the concerns of local communities.

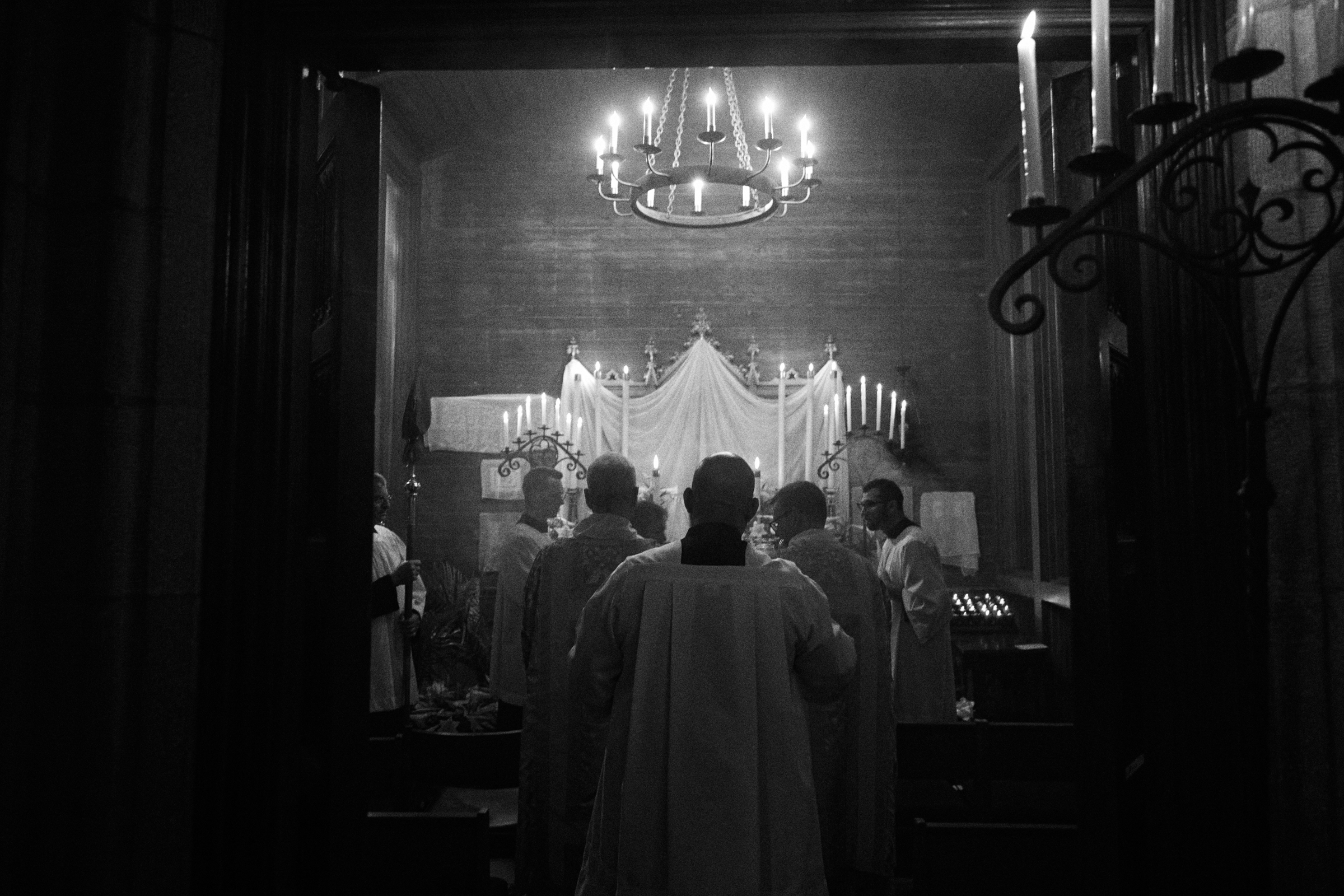

Often when I arrive in a community or event, I do not initially make any photographs. I may have my camera visually present, but do not lift it to my eye until after I have been presented to community leaders by someone trusted and we have shared coca leaves, the societal binder. Not until I have the blessing of the community do I begin to make photographs, and there have been many times when I put down the camera if I feel it is intrusive even if it means missing an important photo. I also share booklets I have created of the project with the communities I work. I am pleased to say that the narrative has been well received and appreciated.

What do you hope people (especially outside Peru) will take away from this work in terms of understanding culture, environment, and the relationship between the two?

As dominant and successful as Western culture has been in recent times, it is still only one way of viewing the world. The current state of the world makes it quite clear that we do not have all the answers. If we are going to change and if there is hope for humanity, we need to understand and learn from one another. Other voices, like those of the Andes, deserve and need to be heard. The few places on the planet where biodiversity and ecosystems remain healthy are in areas that are self-managed by indigenous populations. Perhaps it is time for others to hear what they have to share.

What major challenges have you faced while working on this project in the Peruvian Andes?

This project has been completely self-directed, so not having an editor to work with regularly and consistently has been difficult at times. When I see the work regularly and know the narrative in my mind, I worry I miss the visual holes in the narrative, and need an experienced outside observer to lend some perspective and guidance. Of course, we all know that financial support is very limited these days, so funding has been an ever present challenge. I have self-funded this project, in fact, I sold my home to fund it- gulp. As far as actually creating the photography goes, the biggest challenge has been the language barrier, but I have built strong and lasting connections with people here, some of who speak Quechua, Spanish, and English who assist me. Finally, gaining access to many of the regions and communities poses its own set of challenges. They are often quite remote and communication and planning visits is not easy. So it requires plenty of time and patience.