Lake Powell

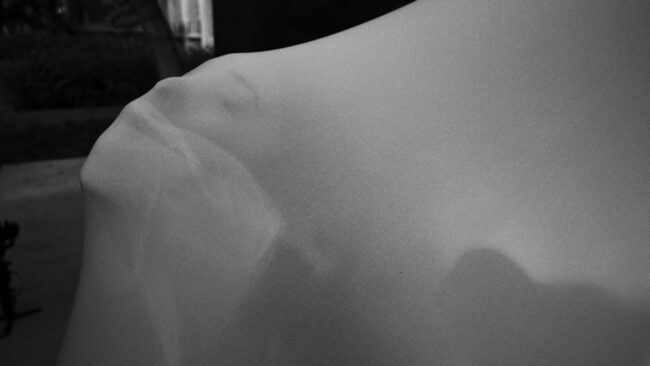

Heidi: Why did you choose to photograph this only in black and white?

Forest: My entry point into the photographic world was, at a very young age, through the alchemical space of the black and white darkroom. It was a place that shaped the foundation of my vision, and my way of seeing in the world. Over the past two decades I have learned to work in color, and it has served me well for interpreting editorial and commercial assignments in the mode of the times. I have always however, reserved a special place in my practice for black and white, a place that I most often visit when I am working on personal stories. It is a way of seeing and working that helps distill the world around me into essence, light and form.

Was it exclusively shot on film?

Yes – all of the work was shot on film, a mix of medium format and 35mm.

How did your connection to nature, movement and climate work inform this work?

There’s a lot in that question. My work and interest in the human relationship to nature and our effect on the climate goes way back. As does the process of movement through land as a way of coming into conversation with it. Growing up as a kid roaming game trails in the mountains around our home, and later working in the outdoor industry climbing and running and navigating rivers, movement across land has always connected me to a deep source of intrigue and creative inspiration.

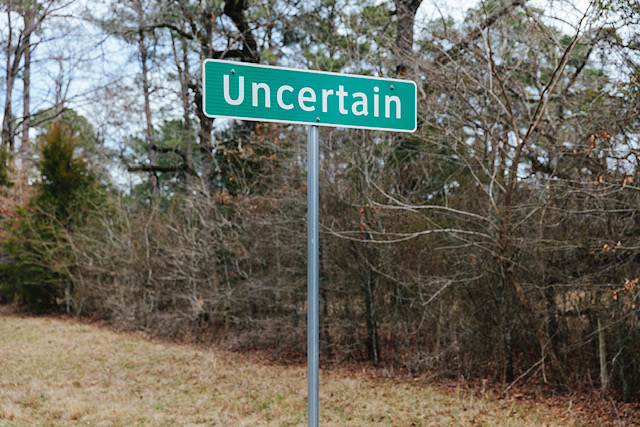

Today so much of the work I encounter in the world comes from a place of talking about nature, about the human effect on climate, about what projections of past and future show us. Those stories are important. But I also think we need more stories that are in conversation with the land, that are informed by a process of immersion, a reappraisal of the importance of emotional and immersive relationship to specific biospheres. Lake Powell is running dry, the West is in a mega drought, Glen Canyon was drowned. These are things that we know – that the data reveal, that science supports, and history has catalogued. These facts are important to consider – they will shape the decisions we make going forward, the policies and actions we take both individually and collectively.

But beyond what can be extrapolated through the analysis of data sets in an air conditioned office in DC, I am interested in what the landscape might offer when it is involved in the conversation in a less abstract manner. This is where the “movement” comes in. The idea of immersing in landscapes and spending long periods of time moving by foot (or in this case by paddle) across the land. It is in this way of moving, watching, listening and interpreting (through words or images or other creative expression) that allows (in my mind) a more nuanced and emotionally vibrant conversation to emerge around the human relationship to the land.

This was an immersive project, you did the writing as well as creating a body of work, what did you enjoy about that process?

Yeah I really enjoyed that way of working. There are some encounters in a project like this that call for a photograph, others for a words. Rarely do I find a single mode of working is the best for all situations. To have the opportunity to weave words and images together, to let them inform and come into conversation with one another allowed for a more relaxed and honest approach. Neither medium was asked to do more than I could will it to do, but through the relationship created between words and photos I feel at times a third creative form emerges in the space between them.

What did this 130 mile packraft* journey teach you about yourself as a creative?

(*it was a mix of packraft and sea kayak and hiking)

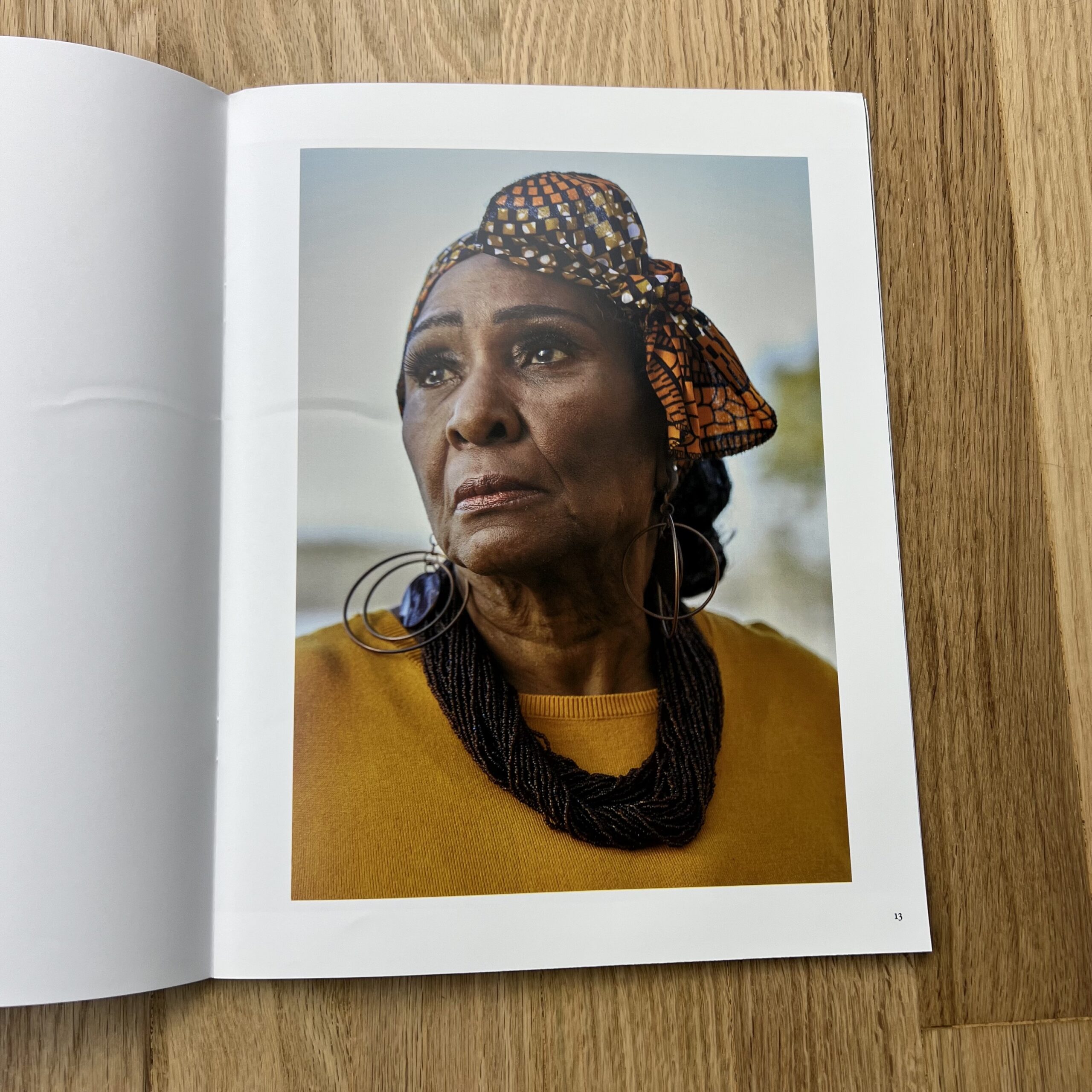

This project in particular was a good reminder to carve out longer periods of time to immerse in a landscape, to return multiple times, and to remain curious. I did a lot of research and reading prior to embarking on this project, and so came into the project with a lot of preconceptions. That was fine, important even, but then the work becomes letting go of those preconceptions in order to see what is actually there. This project reaffirmed my beliefs that the best pictures are not the ones that we set out to make – but rather the ones that find us along the way.

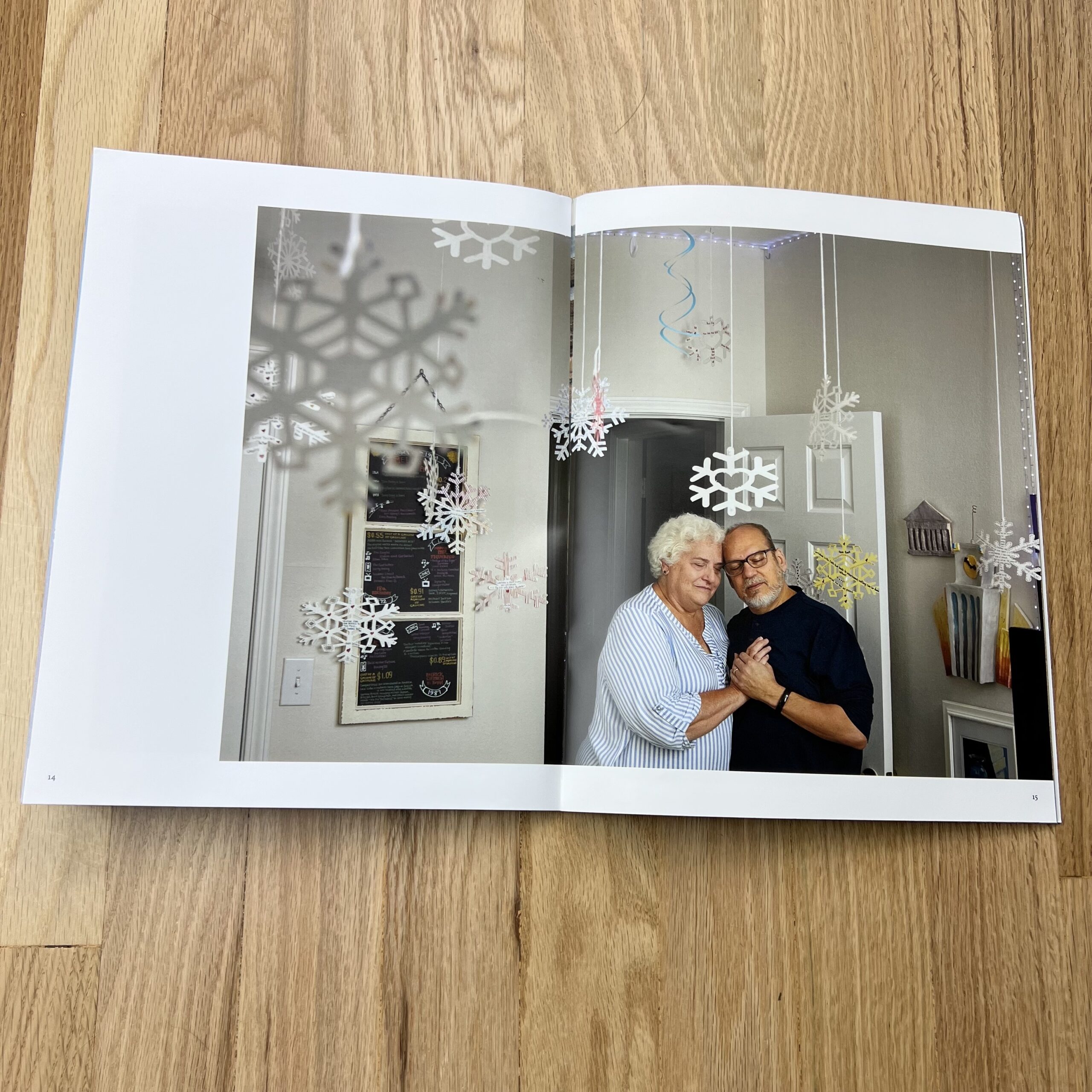

My role as a creative is to be disciplined and in touch with my craft in a way that allows it to be a nearly subconscious endeavor. This requires research combined with a technical and physical proficiency with the tools and in the landscapes being navigated. And then, those foundations being set, it requires a letting go, a release of preconceptions in order to actually be present and tuned to the complexities of that which is being experienced. Experiencing. In the rare instances that this is achieved I think the result is to make work that is honest. To me, that is the highest calling of the creative.

What would you tell your younger creative self?

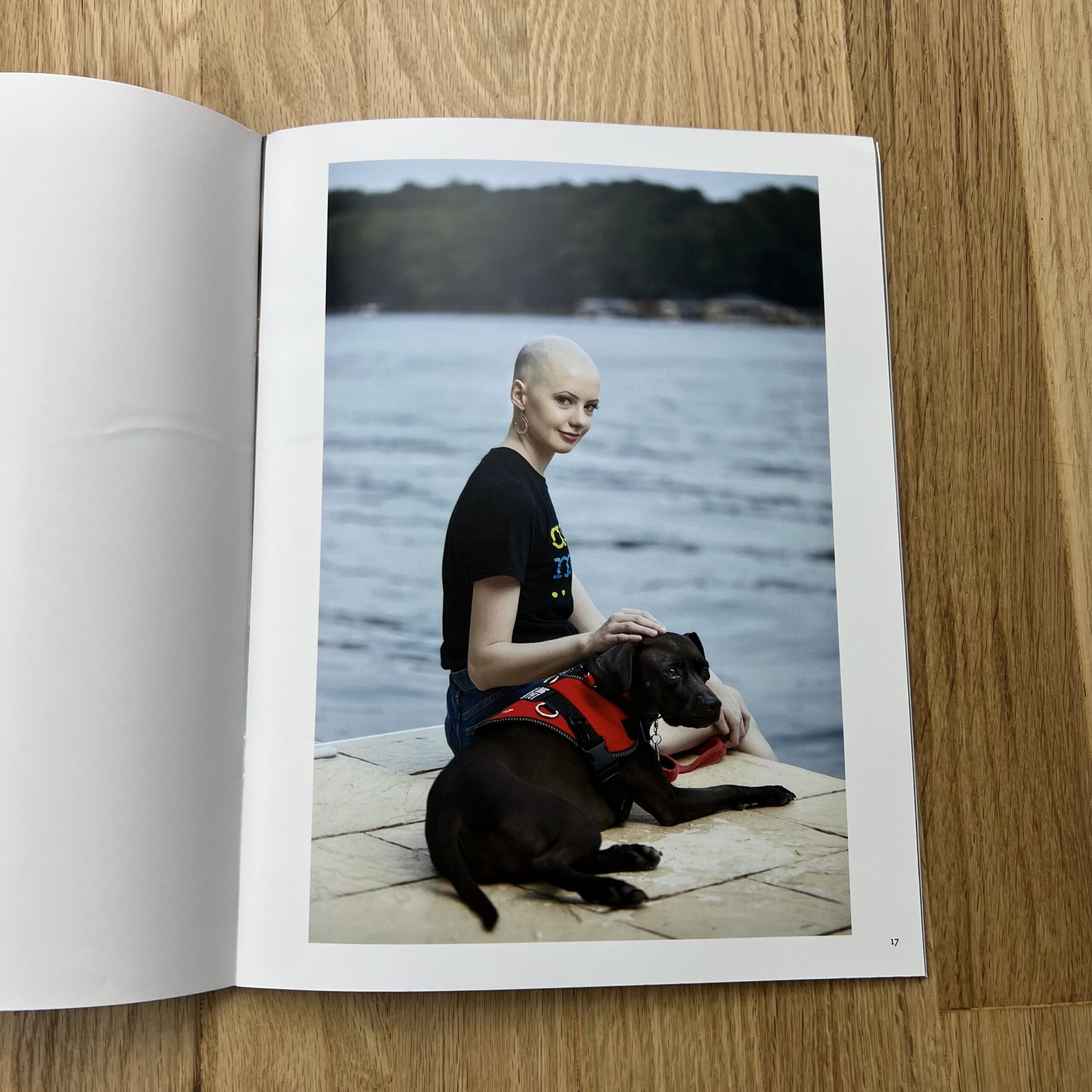

I think actually I’m going to take some advice from my younger creative self, and give it back to my older creative self today. This is from the interview you and I did a few years back for aPhotoEditor, and it grows more true to me with each passing year:

“Do good work. Be kind to the people around you, and to yourself. Balance your idealism with healthy doses of action. Embrace failure and continually seek opportunities to learn – in whatever form or medium they might take. Question societal definitions of success. Make your own. Surround yourself with good people. And be one, as much as you can. Watch, listen, and when the time is right, act with conviction. Be willing to adapt, to move with the currents, to see from different angles, but don’t ever give up on the unique point of view that makes you you.”

Lake Powell

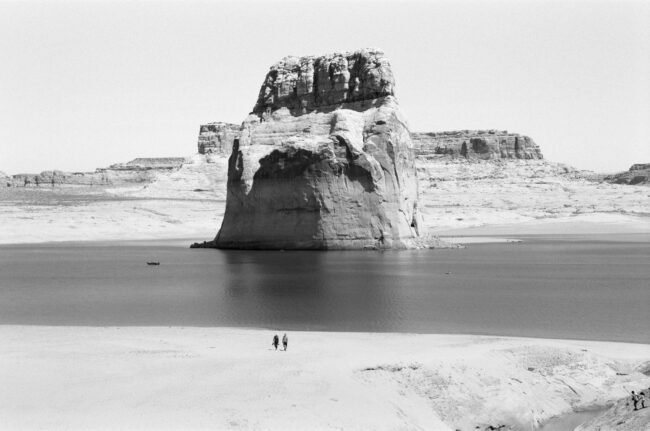

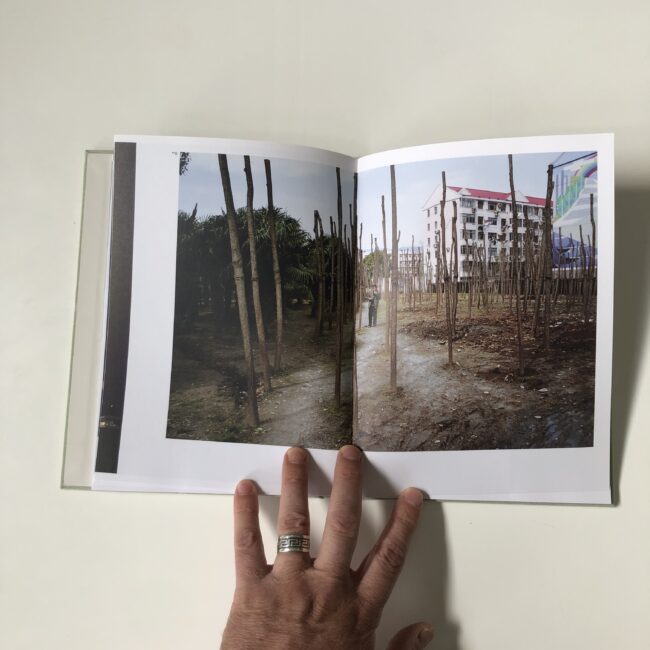

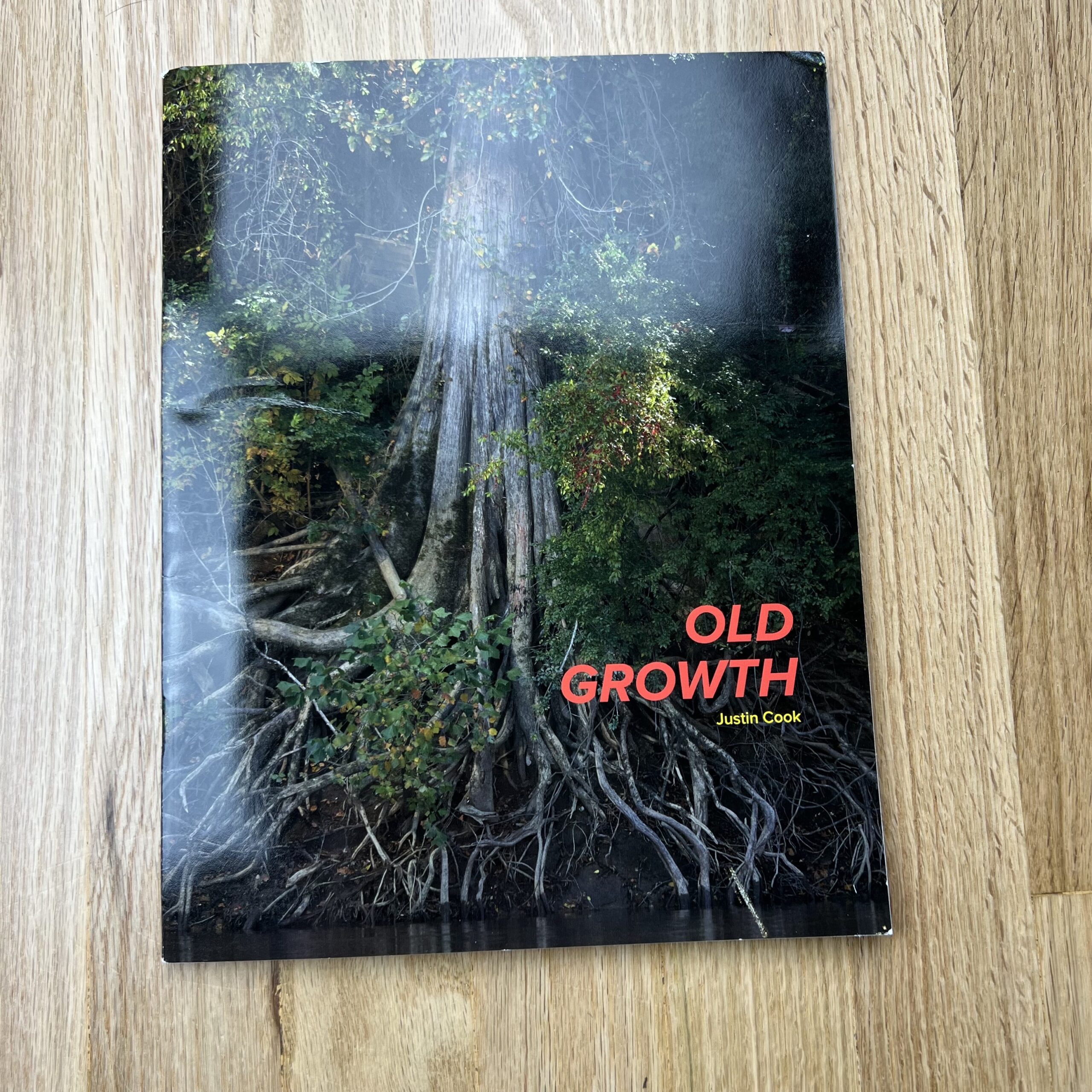

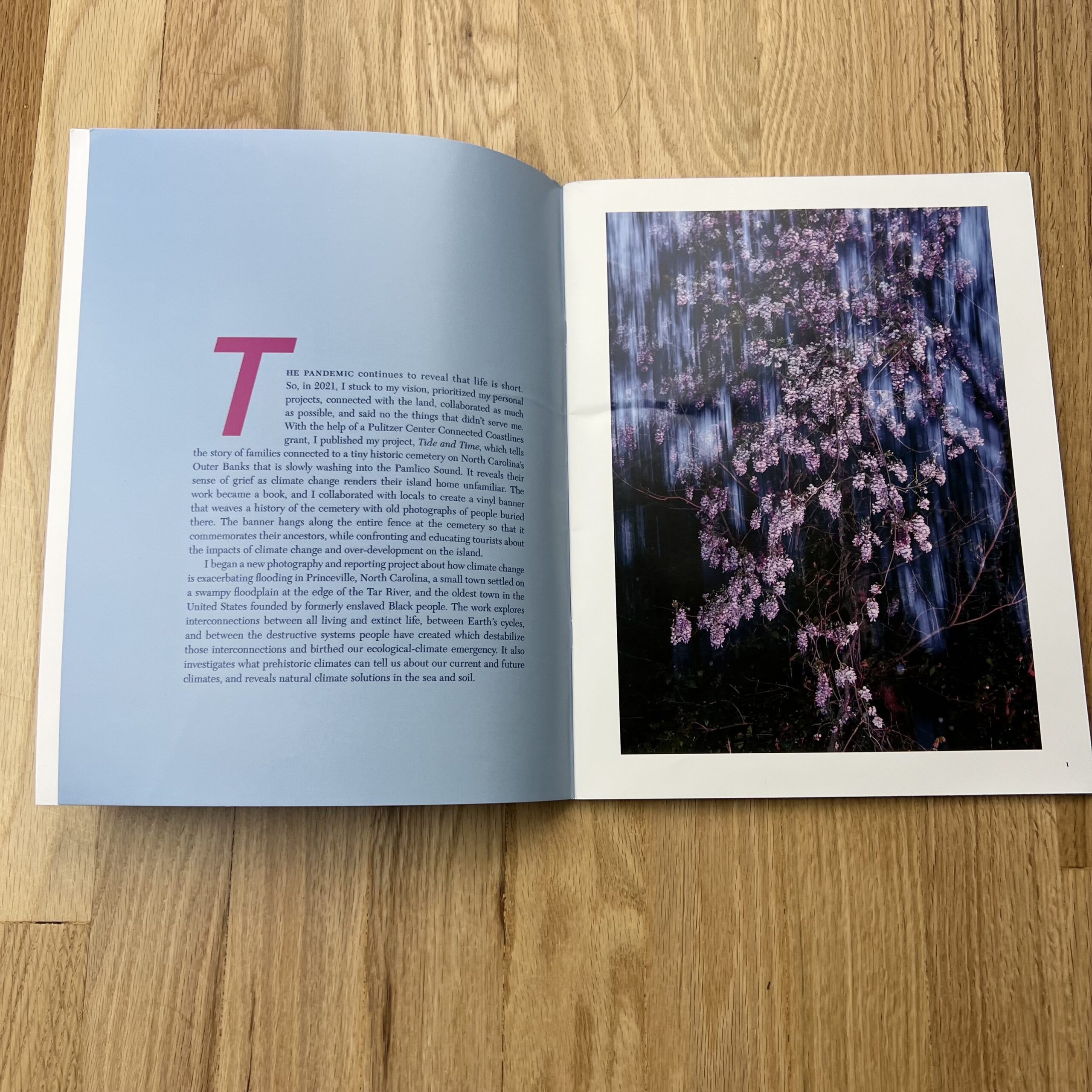

In the spring and summer of 2021, as Lake Powell plummeted toward its lowest recorded water levels since reaching full pool in 1980, Forest Woodward set out on a long unscripted meander through what was once Glen Canyon. Over two visits, in April and July, he sea kayaked and packrafted some 130 miles of the lake as the Colorado River muscled again through long-buried side canyons. When these images were made, the lake surface was between 3,565 and 3,559 feet, on its way down to this spring’s low of 3,522 feet—dangerously close to the level, at 3,490 feet, when the dam may no longer generate electricity. This April, the Bureau of Reclamation announced a plan to push more water down to the lake from Utah’s Flaming Gorge Dam, 730 miles upstream, while simultaneously slowing releases out of the lake from Glen Canyon Dam. Climate and drought may ultimately have the last word on Lake Powell’s future. Until then, these pictures and notes are Woodward’s attempts to hold on to threads of tangled beauty and the strange markings of a shifting world.

Images and words By Forest Woodward

April 4, 2021

I slept by the river last night. Smoked too many cigarettes. I watched a translucent spider weave a strange dance and woke to the Paria greeting the Colorado, the laughter of kindred currents gurgling downstream. Condors dozing, wings wrapped in clay, dreaming Pleistocene dreams in the cradle of a brown god that never sleeps. Breakfast in Page. Last-minute supply run, sunscreen, mezcal, apples, oats, coffee, jerky.

I have four days and a packraft, and I am fairly open to seeing where the wind and my stubby craft will take me. Emergent design if you will. In 2015, I sea kayaked 90 miles from Hall’s Crossing, on the lake’s western edge, to Glen Canyon Dam, and these two trips will mean I’ve paddled it end to end. A rather arbitrary achievement, and one that takes no account of the most interesting part—that the landscape here is never the same twice, and each canyon holds its own beauty and melancholy.

I walk out to a spot below the dam where someone not too long ago sat amidst the hum of turbines and carved the outline of a buffalo into the rock, along with an inscription that everything that was grasped by man would one day be free again. But now it’s gone.. Erased from the soft stone along with all the other marks of passing. I watch a canoe pick its way up the Colorado towards the base of the dam, slow strokes against deep current. It looks cool down there in the shade of the canyon, where the water moves again.

4.8.21

The body of a dead cow lies decomposing in the mud at the water’s edge when I arrive at Farley Canyon, on the north end of the lake. Even in the dark, I can see evidence of a struggle. I wonder how much this scene resembles what John Farley might have encountered when he ran cattle here back in the 1880s, when the Colorado River flowed free.

Trying to pinpoint the exact confluence of river and lake is a moving target, but Farley Canyon seems as good a launch point as any. Before the reservoir flooded this area, Utah State Route 95 crossed the river here, and I figure I can put in at the mouth of the canyon. In the morning, I push off past the dead cow and a couple fishing for largemouth bass. Swamp Donkey Jill, one introduces herself, and offers me some live bait. “Usually the lake’s coming up a foot a day right now,” she says. “It’s sad to see.” She motions towards the mud rings that stretch some 80 feet up from the water’s edge. It’s hard to imagine that a post office and general store sit somewhere under all this silt.

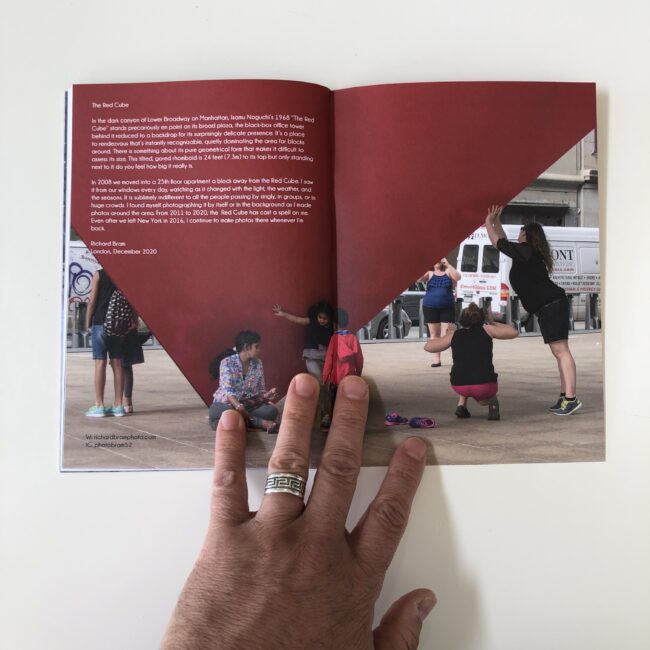

I paddle for a mile, only to find that this finger of the reservoir is orphaned, cut off from the main body of Powell by the receding water. I pack my boat up and hike across mud flats. I check my GPS. It shows me in the middle of the reservoir, surrounded by water on all sides. I look back down at the cracked mud below my feet and walk on, avoiding bubbling sinkholes and gaping cracks between shifting mud pillars. Eventually I reach water. Water moving swiftly in the form of a river. Still no lake.

Unsure of what lies ahead, I cautiously put in, floating quickly through high banks of silt. After a couple miles, the river widens, rushing shallow and fast across riffles of sand. The movement swirls me into a fitful sort of calm, punctuated by the splash of carp and the awkward flapping of seagulls and pelicans. Bewildered and excited, I paddle on until dark and make camp beneath a large sandstone formation called Castle Butte.

The names we name things are telling of our ambitions.

4.9.21

Nothing is fixed, nothing is quite as it seems. All of the death out here—the cow, the drowned cottonwoods, the fish turned wrong side up—is evidence of that, evidence of how this place is ever so slightly out of balance. It is something felt, that can’t be seen from a plane or a boat. You have to get mired in the mud. Struggle to escape. Clamber up rock after rock covered in sun-bleached quagga mussel shells, razor-encrusted tombstones of the nonnative species that have infested Powell. You have to see the death, smell it, hear the buzz of flies, the stench of stagnation. You must also hear the raven’s laughter and the fighter-jet hum of ducks landing in isolated sink pools, the juvenile heron shitting himself as he cautiously learns to hunt, the trio of otters, the coyote who trots away out across the mud flats, seemingly quite content with the state of things.

4.10.21

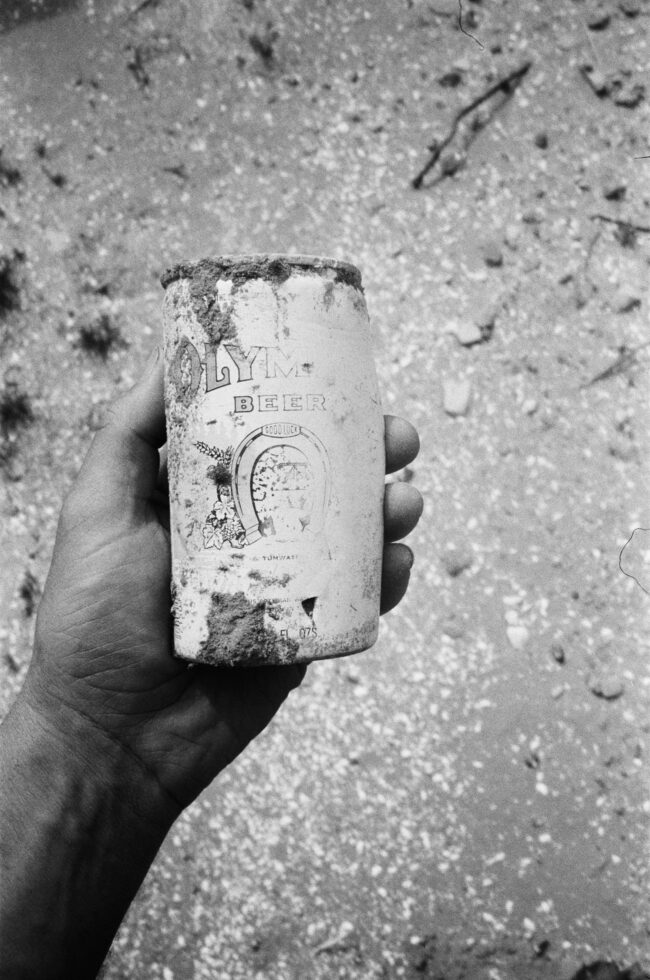

I stop for lunch at a nondescript break in the rocks. Nudge a beer can out of the mud with my foot. Wonder who held it last and when. Turning it over in my hands, one side is bleached by sun and water, the other side looks like it could have been set down yesterday. I can barely make out the words “Good Luck” in faded print below a logo of a horseshoe. Good luck to whom, I wonder? To the person who threw it overboard? To the one who finds it? To the waters that covered it? To the drought that revealed it? To Glen Canyon? To Lake Powell? I flip the can end over end. Horseshoe

up, goodluck, horseshoe down, bad luck. Or is it the other way round? I wonder at this place, at the way it holds paradox. Does a thing have to be lost to be loved, destroyed to be appreciated? I toss the beer can into the bow of the boat. Horseshoe up, let’s hope we catch some luck—whatever that is.

4.11.21

I don’t think I possess the language to properly convey the strangeness of paddling through the desert as cliffs of sand calve like glaciers around you, rounding a bend only to be greeted by flocks of pelicans and a stagnant lake.

From my camp at the confluence of river and lake, I survey an old uranium-mining road running along the base of an imposing band of red Wingate cliffs, leading back to where my truck is parked. I expected to be able to paddle back to my launch point, no walking needed. But there’s a metaphor here about best-laid plans. The need to adapt. What happens when our best-laid plans rest on a flawed foundation? What does the West look like without her brimming reservoirs?

Me, I can just pack down the raft, strap it to my pack, and hike back the way I came. If only everything were that easy.

7.8.21

My packraft had proved about as efficient in the wind-chopped lake as a unicycle in quicksand, and for my trip in July, I find an old British sea kayak on Craigslist and head for the old Hite boat ramp, four miles upriver from Farley Canyon.

There is no lake now, just sand and rock and the muddy muscular flow of the Colorado carrying the last winter snowpack out of the high country. The flow carries me quickly through the layers of lakebed, 30-foot mud gendarmes calving like rotten glaciers into the flow. I stay towards the middle of the channel, bobbing over 5-foot standing waves carved from the sandy bottom. Dust devils tower and dive. A coyote carefully leads her pups down to the river to drink, scrambling away to a safe distance when she sees me. Rich green grasses have sprouted across the silt plain, and a rogue herd of cattle pause their meal to watch me pass.

Later, I will sit quietly at the head of the lake and watch as three otters play on the long mud banks below Wingate cliffs. This feeling of quiet and space will change as I move down into the reservoir, closer to the marina traffic and weekend crowds, but here, in this landscape of flux, I feel acutely aware of my human presence.

7.9.21

You try to come to a place properly. To greet the raven at the canyon’s mouth. To whistle with the wren as she sits on the lone branch. To walk slowly. To look about. There is a gravity to some places that is felt, not spoken or measured. You give a prayer of thanks; whatever that means to you.

I find the first feather in Ticaboo Canyon, a raven tail, and place it as an offering by the dark pool. The second feather is covered in mud, hung up in some branches. Raven wing. I place it in the creek to rest. The third feather is unmarred, as if just left, curled upwards, the down of a dark chest, I think. I hesitate. Look around. Reaching for it, I place my thumb and forefinger gently on the quill. As I lift it, I hear the raucous calls of a pair of ravens watching from downcanyon. I do not know what they are saying. I don’t know the difference between a good and bad omen, only that it is an omen.

7.10.21

I wake to the sound of wind-pressed waves and the sun low but already scorching across the shimmer of the lake. Pushing off , I soon encounter a Forest Service research crew hauling in an endangered razorback sucker, monitoring the spawning range of the fish. There’s a surprising amount of animal life out here. I’m curious how when a landscape becomes less desirable for humans, it might in some ways become more desirable for other life forms.

Animals I’ve encountered on Lake Powell:

Ravens (a dozen)

Coyote and kits

Blue heron

Egret

American koot

Schools of stripers

Osprey

Golden eagle

Egret

Cattle

Sparrow

Bat

Swift

Weasel

Carp-eating clams

Razorback sucker

Lizards, 4 species

Otter

Human

7.10.11

Walking up from the water’s edge in the side channels of Moki Canyon is a walk through the many cultures of spring breakers that have come and gone here. Glow sticks. Sunglasses. Beach towels, a boomerang, ice bags, squattie potties. These canyons are sacred to many peoples, but none more so perhaps than the spring breakers—at least that is if we are to judge by the artifacts. I grew up on stories of Glen Canyon, but even if the reservoir were to fully drain, it would still leave us with a silted shifting world, far from the Glen Canyon of waterfalls and hanging gardens known by the ancestral Puebloans. I kick at a half-buried piece of towel, unearthing a red Solo cup.

It’s interesting how unaware of their wake people are. In one narrow stretch of canyon, a beefed-out wakeboarding boat throttles past me, shouting out a request for directions, which I give them with the motion of a hand. They wave a friendly thanks, disappearing around the bend as their 4-foot wake ricochets off the canyon walls and threatens to swamp my little craft. They mean no malice—they’re just unaware of their effect, the reciprocity between them and water and rock and me. Somewhere in there I suppose there’s a lesson. We all drive big boats some days.

7.11.21

I race a houseboat from Forgotten Canyon, where the ancient Defiance House sits just above the bathtub ring, to Moki Point. I don’t think they know we are racing, but still I win, and that feels good. I swim in the lake—well, I fall in, trying to get water, but it’s my first swim after many trips here, and it feels nice. The lake is a place of reciprocity, it seems. I pick an old Coors can out of the mud, and not ten minutes later am gifted a full Dr Pepper (my favorite!) floating in a side channel. Maybe the canyon is more like the giving tree—giving a place to keep water, then giving the water away.

People talk about caring about the earth, but what they’re usually talking about is caring about a select few playgrounds, curated parks where they climb or bike or hunt. Would we believe someone who said they loved us but only ever saw us dressed up for Sunday service? To really care for something, we’ve got to become acquainted with all sides of it—the dark, the ugly, and the painful alongside the beauty and softness. In my mind, if I’m going to say I love nature, I’ve got to go out and into these seemingly desecrated landscapes and see if I can sit within them, with the discomfort.

I struggle the 12 miles from Moki Canyon to Bullfrog Marina in a heavy headwind and stash my boat in a cove. The bustling energy feels harsh as I walk down the baking asphalt to the restaurant overlooking the marina. I slurp up a cold beer and fork down a salad, watching the Stanley Cup Finals as the sun ripples red gold across pockets of orphaned reservoir.

As I’m finishing my third beer and getting ready to head back down to my bivy bag, an older couple from Salt Lake City sidles up to watch the game. We get to talking about the glory days, decades past, when the reservoir sat high and proud on the land. They’re water skiers, and they tell stories of carving cursive lines across glassy expanses of water under deep redrock walls, secret canyons and sprawling bays blossoming up from dry earth. A place of endless possibility.

The water skiers mourn the reservoir of thirty years ago. I mourn the Glen Canyon I never knew. And while I get the feeling our political beliefs might be polar opposite, we sit here over our beers looking out onto a lake that is now miles away from where it once lapped at this deck, and we agree, this is sad. Ugly, beautiful, changing, and sad.

We agree the water is leaving the West, and something must be done. We agree that as long as this water is tied up in money, it will be difficult for people to agree what to do with it.

We agree that it would be better if more people understood the finite nature of the systems that support life in the American West. Water is what allows us to be here. When it runs out, so does our time on this land.

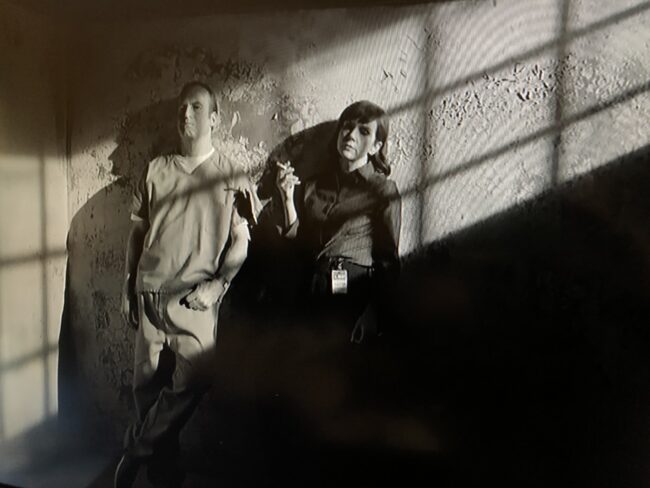

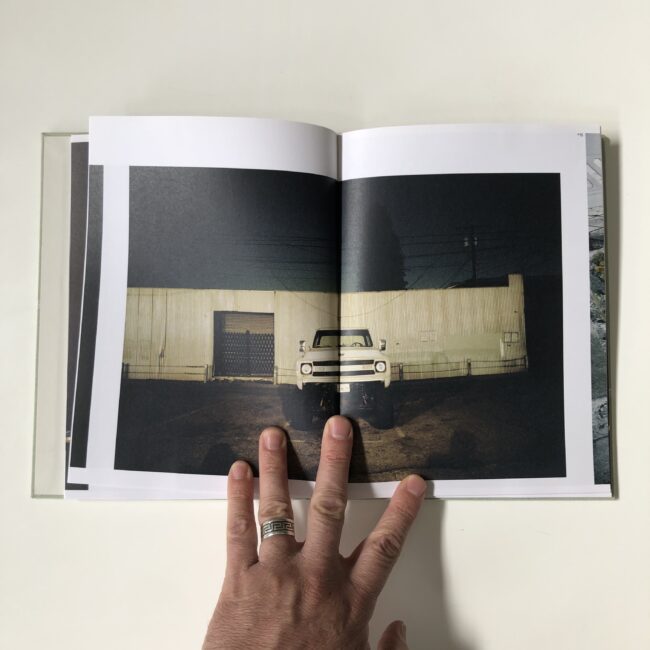

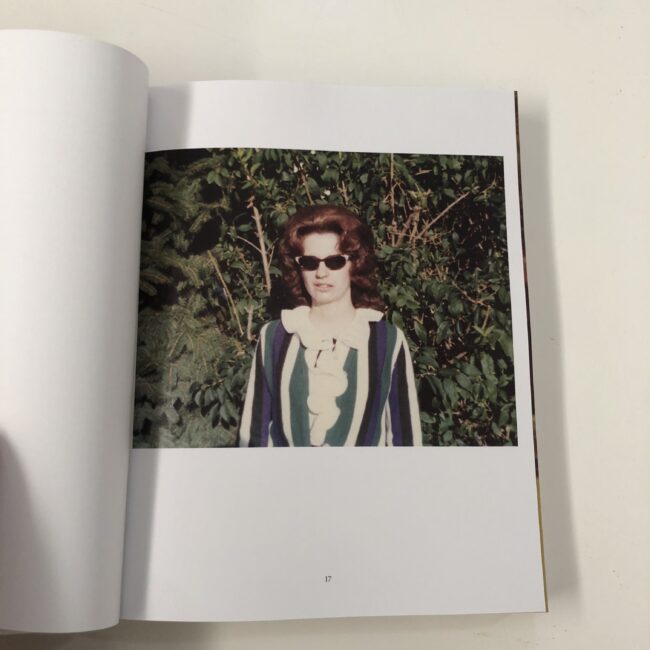

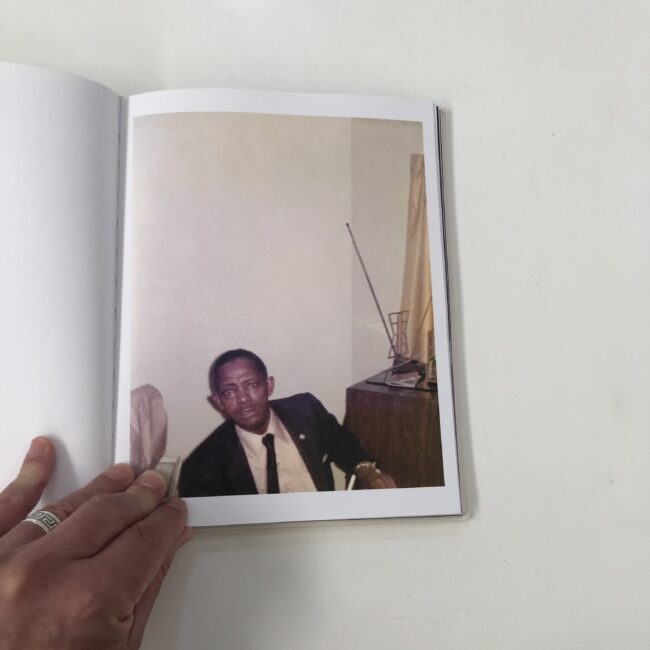

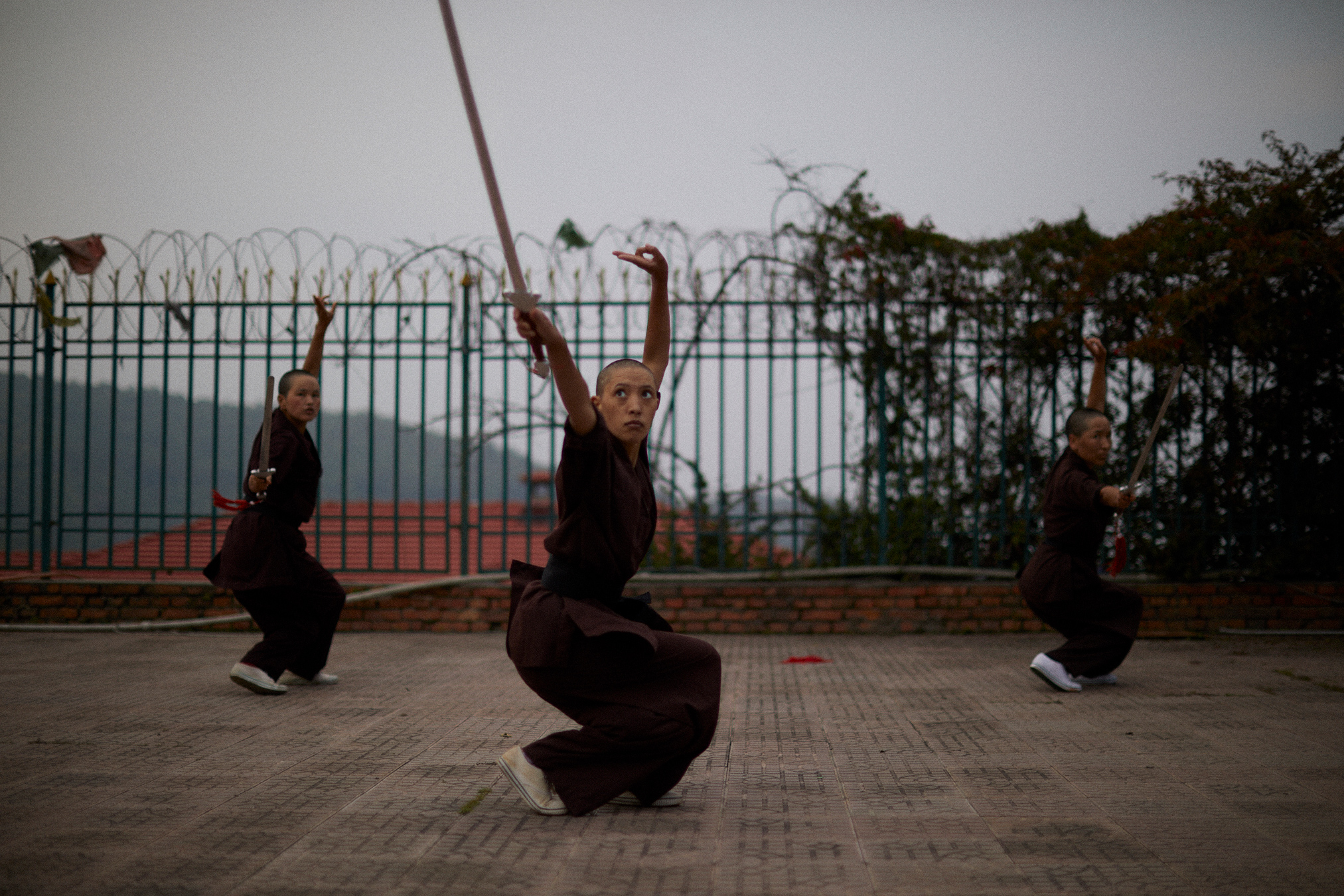

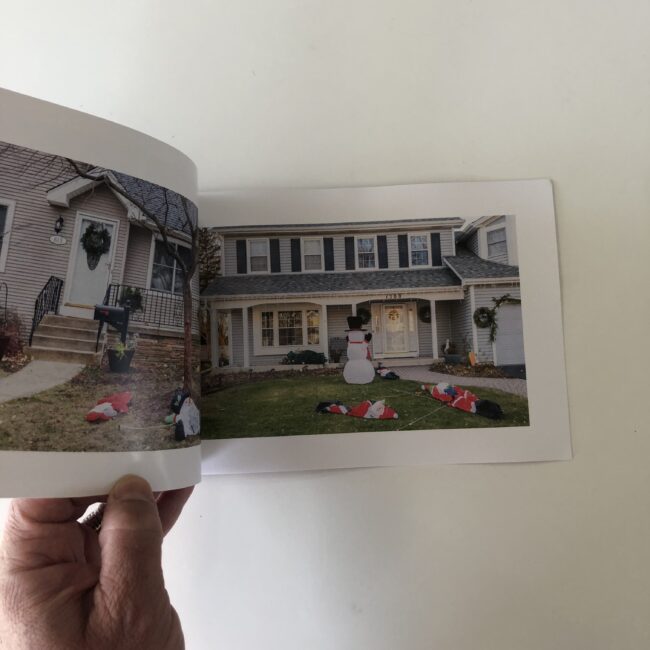

Photograph by Gladys Lou (2021)

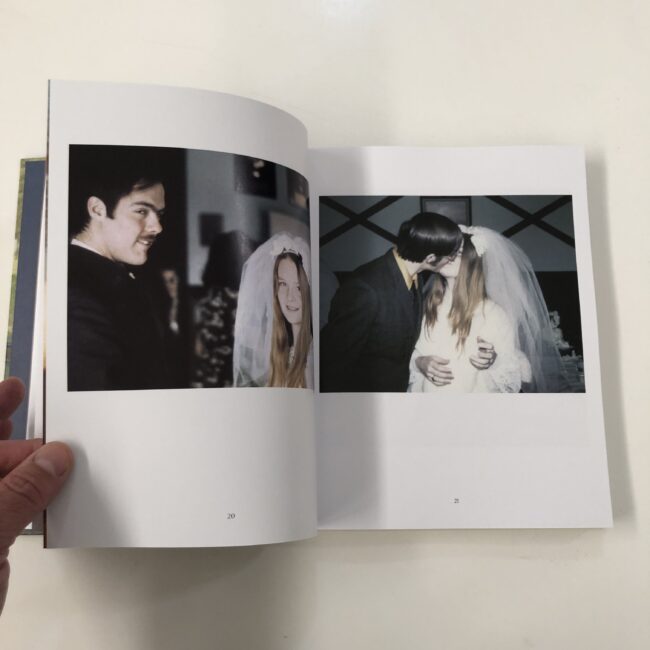

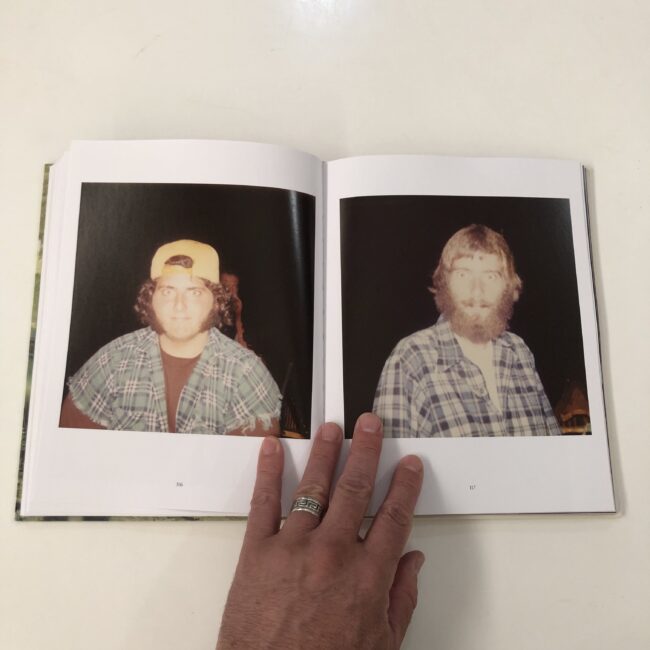

Photograph by Gladys Lou (2021)