Kriston Jae Bethel

Heidi: You studied journalism and political science at Temple University and transformed into a lecture adjunct. How did that academic foundation shape your approach to documentary and protest photography?

Kriston: I think my choice to study both journalism and political science was more a function of who I am and what I want to see in the world, so in a sense, the same thing that drives my approach to photography is what led me to my academics. The two are intertwined, but a core part of who I am is that I like to understand people and I love to learn how things work. I do believe having that formal background allows me to think more deeply about the issues I cover and try, as much as possible, to see what’s unfolding without inserting my own emotions. Of course, as a visual journalist, I’m also trying to capture the feeling behind that, so I can build a connection with the audience. But it also lets me have much more nuanced conversations, which can help people feel at ease or even open doors that may otherwise remain closed.

As noted in Diversify Photo’s “Solutions Photography” talks, trauma-informed long-form story creation is central. How do you ethically build trust with protest participants—especially in emotionally-charged environments?

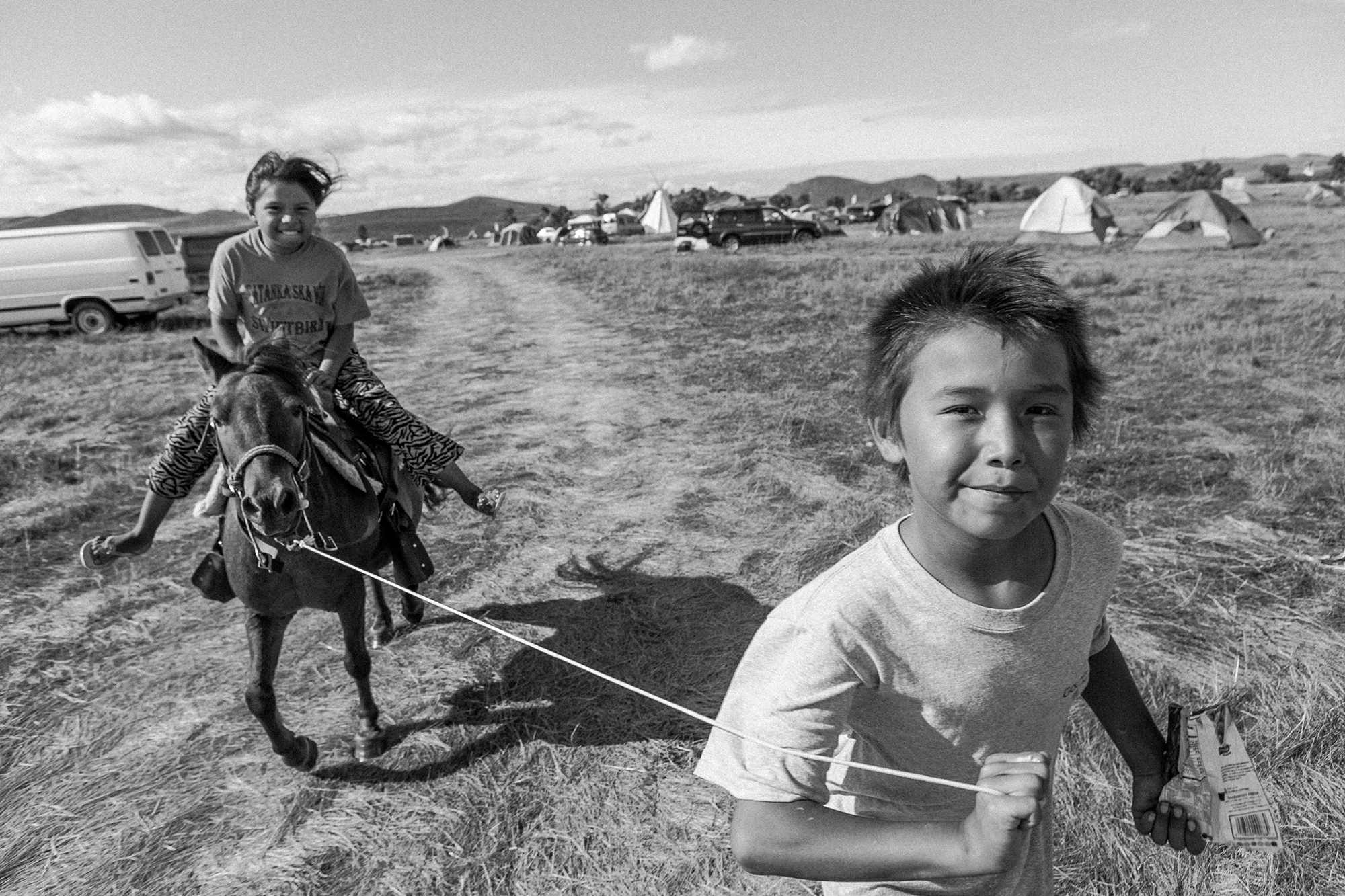

When you’re working in a crowd of people, whether it’s dozens or tens of thousands, I think the first, and hopefully easiest part, is to just be a genuine human being. I take the time to talk to people, I’ll answer questions about what I’m working on, or even make a portrait of someone just because they asked. You’re not there to participate in a protest, but that doesn’t mean you can’t have humanity. I think this is even more important when you’re working with people whose viewpoints may differ from your own. It’s the little things that I think go a long way, even non-verbal communication like a smile or a nod, that help people feel at ease. Authenticity is key.

How do you maintain that journalistic neutrality when covering emotionally charged social justice issues, where public sentiment often runs high?

I think there’s a misconception about what neutrality means and how we handle it as journalists. I mean, nearly everyone wants to believe that they’re neutral, that they’re completely unbiased, that they’re thinking with their head and not their heart. If that were true, politics would probably be a lot more boring and social media would be a much kinder space!

But the fact is that we’re not robots. The important part of being a journalist isn’t that you exist without personal opinions or feelings, but that you don’t let those get in the way of your coverage. We all come with our own life experiences that shape who we are and how we see the world, but when you’re doing the work, it’s important to discern how those may affect your perceptions. I think good journalists learn to allow themselves to feel, without letting it override their reporting.

There are a thousand tiny moments where decisions are made as a photographer – the stories we pitch, where you choose to point our camera, what we leave out of the frame, what makes our final edit. Things like gender, ethnicity, orientation, religion, economic background – all of these qualities shape our world view, giving us unique knowledge and insight. But it’s important to acknowledge these, especially in cases where they may lead to privilege, so we can minimize blind spots.

In high-pressure work, how do you stay flexible—able to fully feel intense moments and then bounce back—and what small habit helps you reset?

Something you and I talked about is this idea of “emotional elasticity” – being flexible with your experiences, your life, your emotions. When talking to my colleagues and friends who work in the industry, a lot of people are feeling the toll of working in a field that’s often driven by high pressure moments, while capturing intense emotions that you’re deeply embedded in. It can be a lot to manage, but it’s important to stay healthy through that. Whether you’re seeing a therapist or journaling on your own, talking it through with someone else or just doing mental check-ins with yourself. For me, I try not to center my entire being around the work, but have outside interests. I rock climb, I coach and overall practice cultivating a positive mindset. I think trying to push things down without recognizing your own experience is a good way to burn out. That’s where the ability to remain flexible and resilient becomes important, so that you can experience everything in the moment, but still come back to who you are.

How do you, as a coach, foster resilience and empathy in your athletes—helping them face failure, handle negative thoughts during long runs, and grow not just as runners, but as people?

I coach high school track and cross country, predominantly working with distance athletes. This is something I do simply because I enjoy being there for them, but it’s a lot less about the athletics than I think most people think. When you have to run a distance event, there can be a lot of time in your head for negativity to creep in and take over. What we try to teach is resiliency, the ability to overcome, how to come back after failure. It’s not about never having those negative thoughts, but how you deal with those emotions. These are the lessons we’re really working on and sport kind of just comes out of it. I hope the thing they’ve learned after graduating isn’t how to be a better runner, but how to be a better version of themselves.

There really is a tremendous amount of pressure on young people today. I think we’re suffering as a society from a lack of empathy and willingness to actually listen to one another. This has us pushing further and further in opposite directions, looking for confirmation more than critical understanding. Combine that with the internet and social media that allows us to see what we want – this has us in a very challenging position right now. Bringing it back around, I hope that my work helps us build a more resilient society, that helps us grow closer together, to see the tough things and understand more about what the other is feeling.

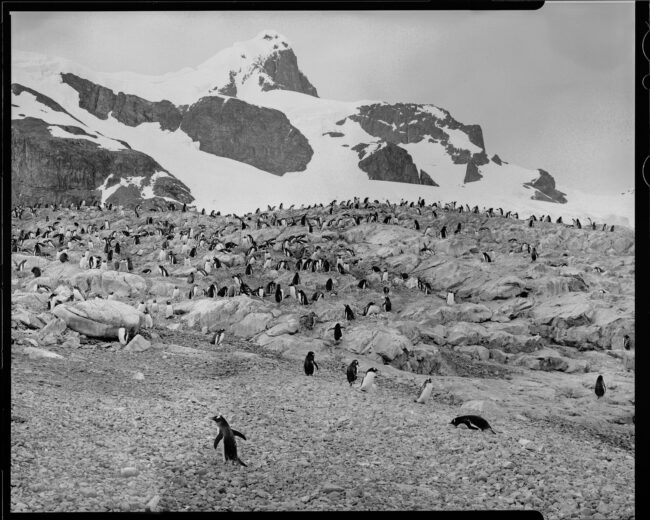

You were embedded in the flagship Philadelphia action, among an estimated 80,000 protesters on June 14. How did you ensure your images reflected both the collective voice and the individual stories within such a massive crowd?

Scale is always impressive and often provides a sense of how important or urgent an issue may be. It’s the big picture. However, it’s also crucial to take viewers into the ground level and create images that capture emotion (something I seem to be talking about a lot). I’m constantly looking through a crowd and trying to find a variety of emotions and moments that tell us how people are feeling. There’s always something that stands out to me. And in addition to that, I’m always trying to find something that may subvert expectations. I’m not always successful, but It’s definitely something I’m keeping an eye out for.

Crowd density and police presence bring unique risks. How do you assess and manage personal risk while on assignment—especially in fast-moving situations?

I want to preface my answer by saying I’m not a HEFAT (Hostile Environment First Aid Training) instructor and anyone looking to learn more about how to stay safe in potentially hostile environments should definitely look into taking a course. That said, there are a lot of steps you can take to keep yourself safe, but the first thing to know is your level of risk tolerance. You have to be honest with yourself about how much you can handle, depending on your training and experience, and to not exceed that. Then you have to have a risk assessment. Who might be working against you, what threats do they pose and how do you mitigate that. In regard to physical safety, having eye protection, head protection and respiratory protection are all things you should have on hand.

What are two key things to consider for anyone covering fast moving situations?

I think the two most important things are 1. Good communication and 2. Having a field buddy.

To the first part, always talk to your editors about your plan, then remain in communication with them throughout the day. And if you’re going into something alone, make sure you have someone at home to keep updated. This could be a partner, friend or family member. Before the protest, I reached out to several other freelance colleagues that were going to be covering the protest and got us all in a chat with one another. While we were all working for different publications, I wanted us to all be able to rely on one another on the ground. This was all in addition to remaining in contact with my editors and security team.

To the second part, having someone in the field with you that you can rely on really does increase your safety level. During the protest, my colleagues and I checked in with one another throughout the day and later in the evening, many of us traveled together, so no one was alone. Things can get more unpredictable when it starts getting dark. A group of protestors separate from the “No Kings” event gathered outside the Federal Detention Center and marched through the city, leading to some conflict with law enforcement. Having someone that can see the things you miss, especially in situations like these, could be the difference between going home and taking a trip to the hospital.

There’s a lot more that can be said about this, like maintaining situational awareness, deescalation (whether it’s with protestors, law enforcement or just someone on the street), when to blend in and when to stand out, but I would highly recommend taking a course for those interested in pursuing more of this type of work.

At the end of the day, the number one thing to remember is to use good judgement and avoid risks beyond what you’re prepared for, because you’re more important than a photo.

###