Calla Fleischer

How did you decide which images or stories would make it into the final volume?

Calla: This was an enormously difficult task. My catalog is made of thousands of images taken over many years. I worked for several months both on my own and then with the help of Greg Gorman to reduce it to a few thousand and then again with Gary Johns to get it down to these few hundred chosen. Some of the images called for others to go with them to create a story. I could easily have made a book of completely different stories, but it would have the same feeling. I could also have made a book with no stories—just beautiful images—but that would be something else altogether.

Your artist’s statement mentions exploring where “culture and humanity intersect.” Can you share a specific image from the book that best embodies that intersection for you, and what the backstory was?

My Portugal project probably embodies this best. I have for several years photographed women in the rural north and urban south to show how women struggle. Their human struggle for survival has parallels in the centuries-old tenant-farming culture of rural northern Portugal and in the sexual commerce of Lisbon. They must get up each day and make it to the next. They have very little support. The men aren’t much help, if there are any. They are captured by circumstances, but the cultures in which they live are completely unalike. Two of those images are the 99-year-old woman on page 295 and a sex worker on pages 284 and 285.

As someone born in South Africa and now living in New Hampshire, how do your personal journey and identity shape the way you see, photograph, and interpret other cultures and lives?

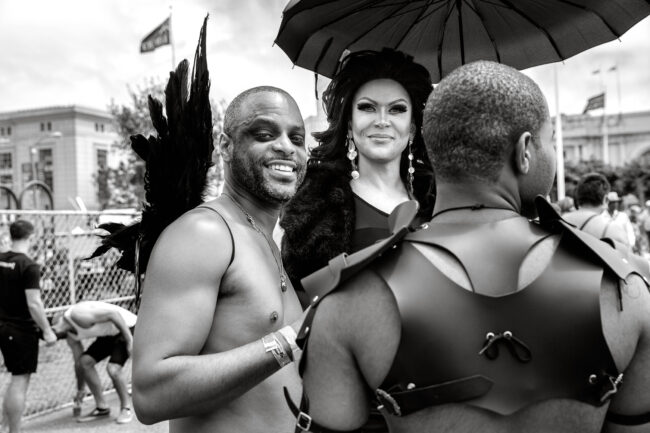

I have lived in South Africa, England, Hong Kong, and the United States—and within the U.S., in New York, California, and now New Hampshire. In each of these places I have had to adapt: to see, feel, and read the local culture rather than brandish my own perspective, and to make new friends on their turf. Perhaps it makes me more sensitive, more of a chameleon, more able to relate one-on-one. I think this led me to be the kind of photographer that can hang back and wait before picking up my camera.

Were there ethical or emotional challenges you encountered while photographing in communities or places far from home? How did you navigate consent, representation, and vulnerability in those moments?

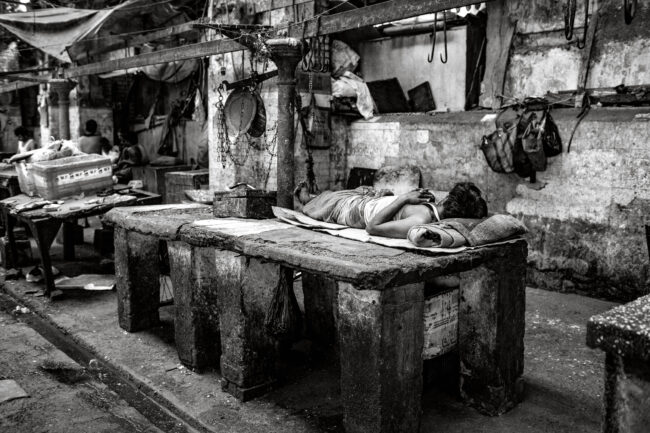

It really doesn’t matter how far from home I am. Many—or even most—of the people I have photographed are grounded in their own cultures and not part of mine. I respect that, and I try to capture aspects of their humanity despite the cultural distance. I wasn’t trying for any specific representation. These are stories of individuals, or small groups of individuals. None of my work is ethnographic or political. I do not take pictures where I sense or hear any reluctance to be photographed. I learned that lesson as a child when I took a picture without permission and was severely chastised by the subject. I believe I can, with most strangers—through my expression and gestures—communicate respect and a tacit request for permission, and I’m very sensitive to their reactions. You can see it in the eyes. There have been moments where I felt a little uneasy, potentially unsafe, but not many, and I’ve been able to back away when that happened. I’m not trying to steal the image in face of resistance, though I know some photographers do. Of course, in some of the shots taken on the fly or from a distance there’s no explicit consent, but I feel those are distant enough not to be intrusive.

Looking ahead, how do you envision Stories Untold influencing your future projects—in terms of subject, style, or narrative—and what new stories are you most excited to tell next?

I will continue to photograph people as I travel, trying to tell their stories. This project could go on and on, as it already has for decades. I don’t think I need to change it. But I have worked in other genres too, and maybe my next project will be a book of figure studies, celebrating the beauty of the body.

If you could sum up Stories Untold in one emotion or feeling, what would it be—and why?

It would be “sympathetic connection” to the lives I depict. Admiration, concern, inspiration, empathy, respect, wonder, delight — all positive emotions. There’s nothing to hate or to fear or to despise. I would like people looking at my book to feel the same connection and curiosity that I have felt.

In five years, what do you hope someone will say or feel when they pick up Stories Untold for the first time?

Then, as now, I hope people will feel that everyone deserves an audience, and that our humanity transcends our circumstances. Perhaps I’d also like them to give me a pat on the back for having pulled all this together—though that’s a bit self-indulgent, it’s true.

If you could go back to the first destination you photographed for this project, what would you do differently now?

I think I would spend more time listening before photographing. Early on, I was often driven too quickly by the subject and the moment. I had to learn to be aware also of the composition, the light, the mood, as well as the immediacy of the moment. Now I understand that patience reveals deeper layers of a person’s story. I would more often slow down, wait for the light, have more conversations, and allow those connections to shape the photographs in more profound ways. I think I am more confident now so can allow this to happen.

How long is your book tour, and what are the destinations?

The book tour will last about six months. It started in New York at the Leila Heller Gallery on October 9, and will include San Francisco, Sonoma, Los Angeles, London, Lisbon, and Cape Town.